The Fed’s Inflation Problem

As we approach the first rate hike cycle in almost a decade, it makes sense for cash investors to take stock of the state of the economy, as well as the Fed’s view of it. The pace at which the Fed raises interest rates will be important to anyone managing a cash portfolio, and close observation of recent economic trends—especially inflation and employment rates—can provide valuable information about possible scenarios for interest rate increases in the new cycle.

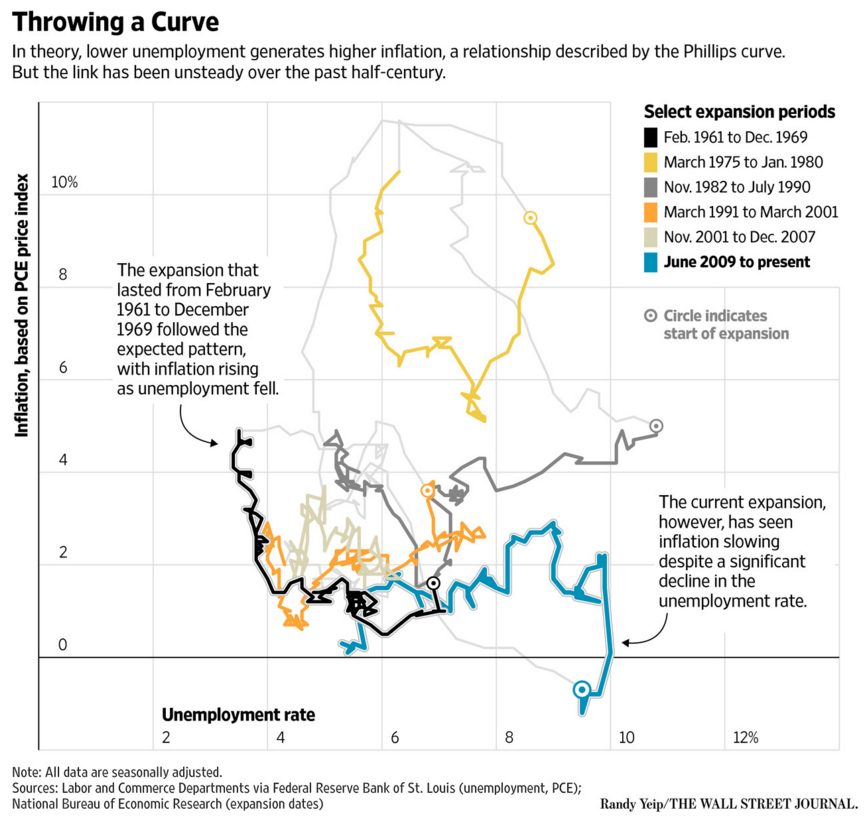

Central to the Fed’s interpretation of recent economic data is the theory of the Phillips Curve. This theory, in its most basic form, holds that increased levels of employment will correlate with higher rates of inflation. It implies that there is a “natural rate” of unemployment, below which available labor in the economy becomes scarce. At this point, firms have to entice workers with higher wages, which eventually feed through to prices, leading to higher levels of inflation. A classic example of this concept is the wage-inflation spiral of the 1970’s. Unemployment fell well below its natural rate, wages accelerated, and inflation reached upwards of 10-15%.

*Graph provided by Ben Leubsdorf, Wall Street Journel, “The Fed Has a Theory. Trouble Is, the Proof Is Patchy”

Over the past few decades, though, the relationship between unemployment and inflation has seemed to break down. Take the current state of the economy. With unemployment at 5.0%, most Fed officials estimate that the economy is, at the very least, close to full employment, yet inflation continues to remain tepid. According to the PCE (personal consumption expenditures) index, prices are up by just 0.2% over the past year ended in October. Even stripping out volatile energy prices, Core PCE is up by only 1.3% over the same time span, a full 0.7% below the Fed’s 2% inflation target.

This conundrum has forced usually like-minded Fed officials to take opposing sides on what they believe will help achieve their dual mandate of price stability and maximum employment. Former Chair Ben Bernanke and current Governor Lael Brainard often seemed to focus more on price inflation, and/or inflation expectations, in considering when to increase interest rates. On the other hand, current Chair Janet Yellen and Vice-Chair Stanley Fischer seem to focus more on whether the labor market is approaching full employment. They have emphasized the role of wage growth in pushing prices back up, circling back to the classic Phillips Curve argument.

What does this all mean for short-term cash investors? Given the tremendous uncertainty surrounding this rate hike cycle, the Fed may be likely to move more cautiously than in the past. Minutes from the FOMC’s October meeting essentially stated as much, with the majority of Fed officials agreeing that “it would probably be appropriate to remove policy accommodation gradually.” Therefore, to take advantage of a slower pace of rate hikes, it may make sense for cash investors to invest in longer duration securities than they otherwise might. Rather than simply investing in a money fund, a separately managed account (SMA) may allow for customized liquidity needs and greater yield potential via a longer weighted average maturity (WAM).

The Capital Advisors Group white paper “Demystifying Separately Managed Accounts: Strategies for a Rising Rate Environment” shows that in past rate cycles, a laddered-maturity SMA had the potential to outperform money market funds over the course of a 12-month investment horizon. With the Fed likely to move even slower than it has in the past, and with upcoming 2016 reforms to money market funds creating even more challenges to their potential performance, it may make sense for cash managers to take advantage of customized segregated accounts as an alternative to meet their liquidity requirements.