With the Fed on Hold and the Yield Curve Inverted, Thoughts on Cash Investment Portfolios

Abstract

The March Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) decision was a major market event that directly resulted in an inverted yield curve. The Fed’s interest rate and growth outlook change echoed other recent moves by central banks that may indicate the end of a tightening monetary cycle. The inverted curve may be an overreaction to the Fed’s surprise decision and not an indication of an imminent recession. We advise caution on portfolio duration and suggest a laddered portfolio to improve liquidity and reinvestment opportunity. The halt to the Fed’s rate hikes could mean a more challenging credit environment. Credit decisions need to be more selective to weather the next downturn.

Introduction

Last October, Fed Chairman Jerome Powell famously proclaimed that the central bank was “a long way” from getting interest rates to a neutral level. After only one hike in December, the Fed declared at its March FOMC meeting that no more hikes are expected in 2019. The reversal ended the financial markets’ guessing game and subsequently resulted in an inverted yield curve.

What were the contributing factors leading to the Fed’s change of heart? What’s so significant about the March meeting? Is a recession coming? How should institutional cash investors respond to the recent turn of events and in their portfolio decisions? We address these concerns in this installment of our investment strategy commentaries.

Figure 1: 10-year vs. 3-month Treasury Yield Spreads

Source: Bloomberg, as of March 28, 2019

How Did We Get Here?

Chair Powell made the “a long way” comment on October 3, 20181, when the fed funds target rate was in a range of 2.00-2.25%, and the Fed was gradually moving to an estimated neutral rate of 3.0%. Fed participants at the September FOMC meeting had a median projection of the rate growing to 3.4% before pausing. They were expecting the fed funds rate to fall in the range of 3.00-3.25% at the end of 2019.

The Fed Chairman immediately faced criticism for his hawkish tone on interest rates, including a scathing Twitter storm from President Trump who nominated him to the post. Bond yields rose, with the 10-year Treasury note briefly touching 3.24% in early November. Meanwhile, softer economic indicators such as lower crude prices and disappointing housing and automobile sales caused worries of an economic slowdown. A flurry of risk concerns also developed, including the lack of a trade pact with China, slowing growth in China and Europe, Brexit uncertainty and Italy’s budget concerns.

Chair Powell quickly reversed his sentiment, noting on November 28 that the current policy rate range was “just below” the Fed’s long-run neutral rate2. Financial markets had a brief period of reprieve from bad news, but pessimism about economic growth prevailed. The yield curve had its first partial inversion between the 3-year and 5-year notes on December 3, generating speculation of a possible recession.

The December FOMC meeting raised the fed funds rates by 25 basis points (bps) as widely expected, but its statement was generally viewed as less hawkish, considering slower growth prospects and the lack of inflationary pressures. Its projection of two hikes in 2019, though down from three at the September meeting, contrasted with the market consensus at the time, which expected no hikes for 2019 at all.

On December 22, the federal government entered the longest shutdown in history, lasting a total of 35 days. Investors sought safety in government bonds, causing yields to drop precipitously, with the 10-year note yield plunging 69 bps to 2.55% on January 3, 2019 from its peak on November 8. Global equities sold off violently, as the S&P 500 and the NASDAQ indices both breached the 20% bear market threshold, making 2018 the worst year for stock returns in the last decade.

Conflicting economic news ebbed and flowed in early 2019. Trade negotiations with China had their up and down days before the Trump Administration backed off from imposing higher tariffs in March. As more confirmations of slowdowns in China and the EU came in, bond yields marched downward steadily. At the front end of the yield curve, a slight bias toward the Fed cutting rates took hold after the January FOMC meeting acknowledged that it would be “patient” and “neutral” in future rate directions. It also floated the idea of treating the 2% inflation target “symmetrically,” meaning it would allow inflation to overshoot the target before bringing it back down. This gesture led to the impression that the Fed might revise the number of its projected rate hikes for 2019 from two to just one.

What’s Significant about the March FOMC Meeting?

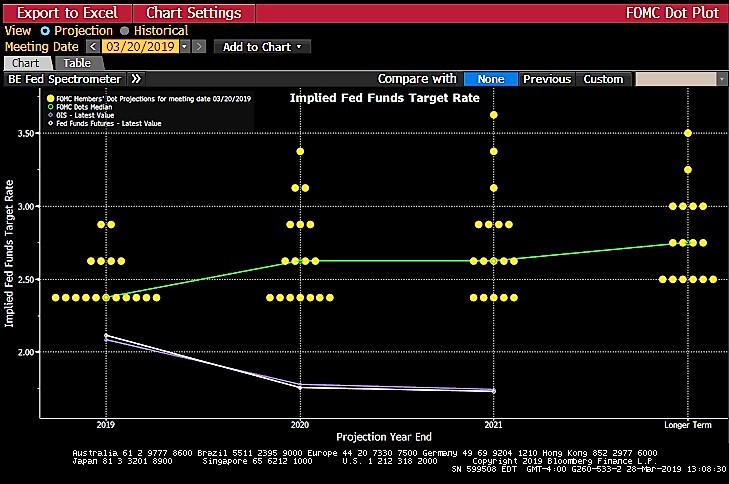

The March meeting was a market-moving event for two reasons; a possible turn in the direction of interest rates and the end of Fed balance sheet reduction both indicated a reversal of the monetary cycle, which had tightened since December 2015. The surprise to the market was how fast the Fed consensus went from two hikes to none for 2019 and how the dots on the so-called dot-plot shifted down between meetings. This was a more dovish signal than most economists had expected.

Specifically, 11 of the 17 Fed officials participating in the Summary of Economic Projections (SEP) survey now expect no hikes this year, up from just two. The new consensus is consistent with the March FOMC statement stressing that the Fed will be “patient” in determining future “adjustments” to policy. The median Committee member now expects barely one hike (2.65% midpoint) in 2020, down from three hikes (3.15% midpoint) at the December 2018 meeting. Relative to the current midpoint of 2.375% fed funds rate, the median long-run dot is unchanged at 2.75%. The positive gap suggests that the current policy is still accommodative.

Figure 2: FOMC Dot Plot – December 2018 (Gray) vs. March 2019 (Yellow)

Source: Bloomberg

Along with a more dovish rate outlook came milder forward guidance on the economy in several categories. For example, the Committee expects GDP growth will slow to 2.1% this year from the 2.3% forecast in the December SEP, and down to 1.9% in 2020 from a 2.0% forecast. It expects the unemployment rate to move higher by 0.2% to 3.7% and 3.8%, respectively, in both years. Personal Consumer Expenditure (PCE) Inflation, however, will tick down 0.1% each to 1.8% and 2.0%, respectively. These revisions of slower growth, higher unemployment and lower inflation threats are consistent with the Committee’s patient and dovish stance towards interest rates.

The Fed also disclosed a plan to halt its balance sheet reduction by tapering down the monthly reinvestment caps for Treasury securities from $30 billion per month to $15 billion beginning in May. Starting in October, no caps will be in place for Treasury securities, meaning all maturing proceeds will be fully reinvested. Also starting in October, all agency debt and agency mortgage-backed securities’ maturities and paydowns above the existing $20 billion monthly cap will be reinvested in Treasuries. Besides reducing reserve drains in the banking system, halting balance sheet reduction will help Treasury debt issuance and the availability of Treasury-backed repurchase agreements, both of which are beneficial to liquidity in the cash market.

We should note that the March FOMC decision came within weeks of the Bank of England abandoning its plan for multiple rate hikes3 and the European Central Bank delaying its first post-crisis rate hike and offering cheap bank loans to revive the eurozone economy4.

The March meeting turned out to be a major market-moving event. Equities staged a strong rally, while bond yields across maturities dropped dramatically. The benchmark 10-year Treasury note yield dropped as much as 32 bps, from 2.59% before the announcement to 2.37% on March 27. The two-year note yield dropped 25 bps to 2.20% over the same period. Short-term Treasury bills, however, were broadly unchanged due to their anchor to the fed funds rate. For example, the three-month bills yield dropped just two bps to 2.43%.

As a result, the levels of the two-year and 10-year note yields are below those on the three-month bills, a phenomenon known as an inverted yield curve.

What Does an Inverted Curve Tell Us?

It is often said that an inverted curve is a reliable forecasting tool for recessions, and it is generally true. Come June, we will have surpassed the longest economic expansion (120 months) in history, so a recession may be long overdue. As we discussed in the January issue, the curve inverted four times in the last four decades, each followed by a recession. However, an inverted curve had no predictive power over the exact timing of the next recession nor market returns during those periods. This is especially significant for cash investors with moderately short time horizons.

How does one estimate the likelihood of a recession? Besides the yield curve, traditional economic indicators such as consumer and business sentiment, manufacturing surveys, retail sales, unemployment and income, housing, and estimates of GDP growth, are not pointing to an impending recession. Surveys of leading economists and market observers, another popular recession predictor, also fail to suggest more than 50% odds of a recession in 2019 or 2020. For example, a survey conducted by the National Association for Business Economics showed 75% of economists think the economy will enter a recession by 2021, but only 10% of them think it will happen in 2019 and 42% in 20205.

As we concluded in our January article, the takeaway from the flat and possibly inverted curve is that it provides a signal of slower growth, which is expected, and a halt to the Fed’s tightening bias, which has been confirmed by the March FOMC statement. It is, however, inaccurate in pinpointing a recession or the next rate cut.

Back to the question of what an inverted curve tells us: generally when investors expect the Fed to cut short-term rates sometime in the future, yields on long-dated securities will drop more than short-dated securities to compensate for lower income potential on future short-term securities. The Fed can, and did, cut rates without causing a recession. For example, the yield curve inverted without recession in 1965-1966 and then in 1998, and the economy continued to grow6.

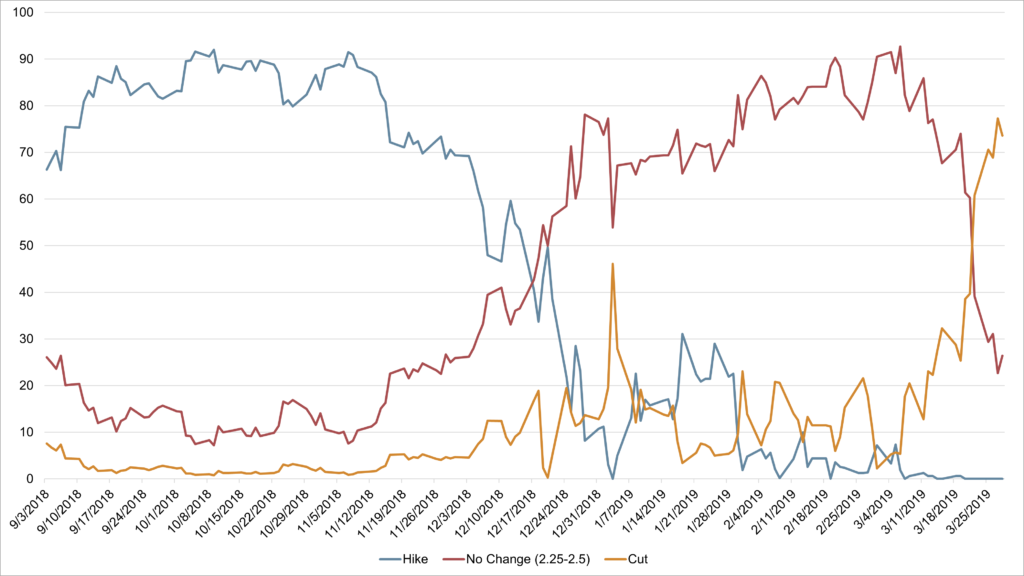

Figure 3: Futures Market’s Indication of December 2019 FOMC Decision

Source: : Bloomberg WIRP Historical analysis, as of March 28, 2019.

Will the Fed cut rates soon? As of March 29, despite the Fed’s indication of no rate actions this year and one possible hike in 2020, the futures market places a 69% chance of a rate cut, and a 22% chance of two cuts, before December 2019. A similar signal is intuitively seen in the 13 bps spread between the one-year bill, which yields 2.39%, and the two-year note, at 2.26%, suggesting a breakeven point of 26 bps if one were to invest in two back-to-back one-year bills relative to the two-year note. Here again, the market appears to take a different position from the Fed in calling for cuts.

Since “hard” economic indicators project a low probability of recession on the horizon, it is puzzling to understand why the market thinks the Fed needs to cut rates this year. A few explanations exist. For one, as the Fed noted in its recent statements, economic growth in the rest of the world has slowed recently, representing an external threat to growth in the US. Developing stories on trade wars with China and auto tariffs also may influence market sentiment. Selloffs in the equities market brought back the chatter of a Powell “put.” Geopolitical headlines such as Brexit, North Korea, Iran, and criticism on the Fed could also influence traders’ projections.

None of these potential causes for concern are new, so the timing of the March meeting pushing long-term rates down to cause an inverted curve should not be overlooked. It is possible that, as the Fed became more dovish to please the market, the market moved further dovish to predict a cut. It is not unreasonable to think that the Fed might have worried about the state of the economy so much to cause them to go from three hikes to zero in a matter of six months. Such can be one of the communication challenges the Fed faces.

To conclude, the yield curve inversion we witnessed in recent days may indicate the market’s assessment of events that could potentially derail the base case growth projection rather than the health of the economy itself. The swift change in the shape of the curve could indicate an overaction to the surprise March FOMC decision. And recent research revealed that the yield curve needs to be inverted on average over a quarter, not over a few days, to prove reliable7.

How Should I Position My Portfolios?

As managers of short-duration institutional portfolios, we are keenly aware of the effect of interest rate gyrations on client portfolios and the undesirable outcome of an inverted yield curve. Unless convinced that interest rate cuts are forthcoming, few investors would be inclined to invest in longer-term securities at lower yields.

Our immediate read on last week’s yield curve reaction to the FOMC decision is that there was an element of overreaction, both on rate hikes and the balance sheet. Should incoming economic indicators continue to point to less robust but moderate growth, we expect the inversion in the curve to become less pronounced.

Whether readers agree with this assessment or not, we advise on a cautious portfolio duration as one weighs the tradeoffs of the possibility of a rate cut projected by the market and a potential hike in 2020 indicated by the Fed. We generally advocate for a laddered separately managed portfolio to improve liquidity and reinvestment opportunity. Altering portfolio duration in a bet on interest rates is a lesser priority than maintaining portfolio liquidity amidst market gyrations.

What is perhaps a more relevant portfolio consideration is what a halt to the Fed’s interest rate decision means for credit investments. Softness in issuances and widening spreads on speculative grade bonds have been in the press for a while, as has the deteriorating credit quality on certain industrial, auto and real estate loans. While a pause in the Fed’s decision may offer some relief to these borrowers through lower credit costs, it is also indicative of a more challenging operating and financing environment in a slower economy. Credit decisions on eligible investments should be more selective in order to weather the next downturn.

DOWNLOAD FULL REPORT

Our research is for personal, non-commercial use only. You may not copy, distribute or modify content contained on this Website without prior written authorization from Capital Advisors Group. By viewing this Website and/or downloading its content, you agree to the Terms of Use.

1Christopher Condon, Jeanna Smialek, and Rich Miller, Powell says Fed may lift rates to levels that restrain growth, Bloomber Markets, October 3, 2018 https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-10-03/powell-says-fed-to-keep-hiking-at-gradual-pace-amid-solid-growth

2Steve Goldstein, Fed’s Powell says interest rates are “just below neutral”, MarketWatch, November 28, 2018. https://www.marketwatch.com/story/feds-powell-says-interest-rates-are-just-below-neutral-2018-11-28

3Chris Giles, Bank of England pulls back on multiple rate rise plans, Financial Times: UK Interest Rates, February 7, 2019. https://www.ft.com/content/479440c4-2acd-11e9-88a4-c32129756dd8

4Francesco Canepa and Balazs Koranyi, ECB Pushes out rate hike, offers cheap cash to banks, Reuters, March 7, 2017. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-ecb-policy/ecb-pushes-out-rate-hike-offers-cheap-cash-to-banks-idUSKCN1QO0MH

5Brittany De Lea, US economy to enter a recession by 2021, economists predict, Fox Business, February 25, 2019. https://www.foxbusiness.com/economy/us-economy-to-enter-a-recession-by-2021-economists-predict

6James Machintosh, Inverted yield curve is telling investors what they already know, The Wall Street Journal: Markets, Streetwise. https://www.wsj.com/articles/inverted-yield-curve-is-telling-investors-what-they-already-know-11553425200

7James Machintosh, Inverted yield curve is telling investors what they already know.