What’s the Deal with Long-Term Rates?

As stocks soar to record highs, it seems as though the decline in long bond yields has been endless. Less than a year after the Federal Reserve saw economic conditions sufficient to warrant the first rate hike in almost a decade, rates on long-term U.S. Treasury bonds now lie at near-record low levels (with the 10-year slightly above 1.50%).

So what’s the deal with long-term rates? The economy is entering one of its longest expansions ever, so why are they near all-time low levels? The exact reasoning is more complex and nuanced than can be fully described in a blog post, but there are at least two overarching factors at play here.

1. Low Growth + Low Inflation

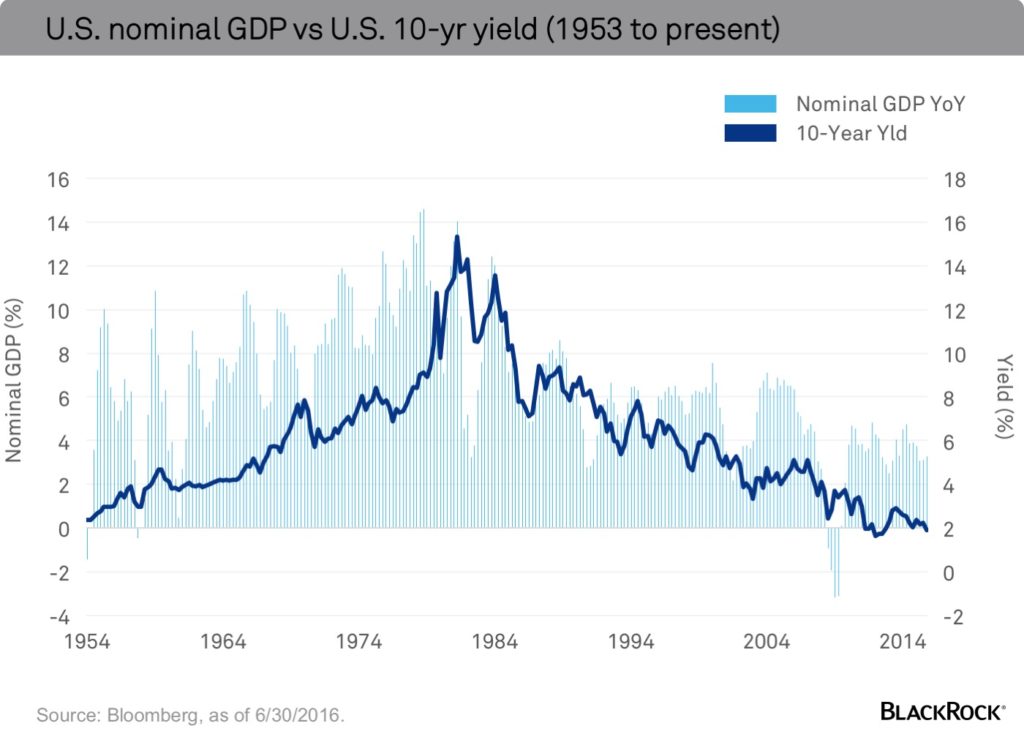

The most important factor in explaining the period of prolonged low interest rates is the decline in both long run growth and inflation levels. This is captured by the level of nominal GDP, which is simply real GDP + inflation. As Russ Koesterich of Blackrock pointed out, NGDP has been on the decline since the early 1980’s, and government bond yields have followed a very similar trend. This seems unlikely to reverse itself in the foreseeable future. While second quarter growth looks to be relatively strong, longer-term weakening productivity numbers suggest that growth will continue at or around its current level. Inflation is a similar story; the TIPS market is currently projecting that it will average only 1.5% over the next decade. One thing that might change this is if the Federal Reserve were to credibly commit to hitting a higher level of inflation, boosting inflation/NGDP expectations. However, with the Fed not projecting to hit its current 2% target until 2018, this is unlikely.

2. Excess Demand for Safe Assets

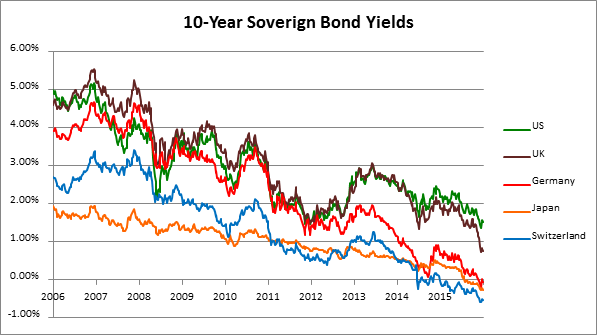

The second important factor at play is the heightened level of demand for safe assets across the globe. As the graph below shows, yields on government debt have been declining for the better part of the past decade. The demand for such assets, partially fueled by central bank bond buying programs, is so insatiable that investors have been willing to endure negative interest rates in order to have a stable place to park their cash. According to Bloomberg, there is now nearly $10 trillion in negative yielding government debt, and nearly 80% of all Japanese and German sovereign bonds have gone negative. Even Italy currently has $1.6 trillion of negative yielding debt.

Source: (Bloomberg as of 7/27/16)

As a result of these factors, foreign capital has begun to flood into U.S. Treasury bonds, which offer not only safety, but also relatively better value. For example, a proxy measure of foreign demand hit an all-time high of 73.6% at June’s auction of 10-year Treasuries. And with low growth and political instability abroad, this trend seems unlikely to change anytime soon.

So with government yields so low, where does that leave cash investors? To start, Treasurers may want to examine whether they can incorporate some corporate exposure into their portfolios. While some corporate bonds in Europe have gone negative, the sector as a whole still offers relatively better value. According to Bank of America, U.S. investment grade corporate bonds now account for a third of all investment grade yield income, compared to 23% just one year ago. One way to easily add this exposure might be to take advantage of a separately managed account (SMA), which can allow for customization to help meet liquidity and credit quality needs. Such an account potentially could allow for increased exposure to the corporate sector without a material uptick in risk, especially if one were to implement a buy-and-hold strategy.