Quantitative Tightening (QT) Is Coming to An End – What Does It Mean to Cash Investors?

Minutes from the December FOMC meeting indicated that some Federal Reserve officials wanted to begin discussing “slowing the pace” of securities runoffs on its balance sheet. Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell confirmed after the January meeting that the Committee will begin formal conversations on the topic at its March meeting. The indication of an end to the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet reduction being in sight drew immediate market attention due to its potential impact on bank reserves, government funding, bond yields, and market liquidity. While more details will come from the March meeting, it may be useful to understand how the Fed balance sheet affects market sentiment and liquidity and how cash investors may want to process conflicting signals.

First, A Primer on the Balance Sheet

Like hiking the federal funds rate (FFR), shrinking the balance sheet signifies monetary policy tightening. A “normalized” balance sheet also gives the Fed dry powder to deal with the next financial crisis. All else being equal, a smaller balance leads to lower reserves, higher borrowing costs, and less liquidity. The buzz around the topic reflects the concern that if the Fed does not “taper” the runoffs soon, financial conditions may become too tight which could cause a liquidity crunch or stall the economy.

Assets held by the Federal Reserve are comprised of Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities (MBS), crisis management loans and credit portfolios, foreign currencies, gold, and miscellaneous items. In the wake of the 2007-2008 global financial crisis (GFC) and during the Covid-19 pandemic, the balance sheet grew through large asset purchase programs (LSAPs), known as quantitative easing (QE), to stimulate economic growth. At the peak in June 2022, the Fed’s balance sheet was $8.9 trillion compared to less than $1 trillion in 2007. On January 24th, 2024, it stood at $7.7 trillion ($4.7T in Treasuries and $2.4T in MBS).1

Currency in circulation, reserve balances, and the Treasury general account (TGA) were the main pre-QE liabilities. The Fed added a new tool in 2014, the Overnight Reverse Repo Facility (ON RRP), to help move market rates in tandem with the Federal Funds Rate (FFR) available to banks. In June 2022, total liabilities (always equal to total assets) of $8.9 trillion consisted of $2.2 trillion in currency, $2.5 trillion in RRP, $760 billion in TGA, and $3.1 trillion in reserves. As of January 24, 2024, total liabilities were at $7.7 trillion ($2.3T currency, $980B RRP, $815B TGA, and $3.5T reserves).

Ending Runoffs Is Similar to Ending Rate Hikes

The market is excited over the prospect of an end to balance sheet runoffs likely because it affects capital markets in a way that is similar to the Fed ending rate hikes, albeit on a smaller scale. Three months after its first hike, in June 2022, the Fed began a balance sheet runoff schedule to let up to $95 billion securities ($60B Treasuries and $35B MBS) mature without reinvesting, thus gradually reducing its size in a gentle form of quantitative tightening (QT).

The mini rate hike effect from QT is a subject of much debate among economists. Bin Wei, a research economist at the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, estimates that $2.2 trillion of passive runoffs over three years is equivalent to 29 basis points of rate hikes during normal times, and 74 basis points in choppy markets.2 Applying this estimate to the $1.2 trillion balance sheet reduction since June 2022, the operation has had the equivalent effect of 15 basis points in rate hikes. This would suggest that the interest rate effect from quantitative tightening is quite mild.

There is broad consensus that the Fed needs to stop shrinking its balance sheet before financial conditions become too tight resulting in monetary policy and financial stability implications. The December FOMC minutes indicated that some Fed officials wanted to start working on “technical factors that would guide a decision to slow the pace of runoff well before such a decision was reached in order to provide appropriate advance notice to the public.”3 The message is that ending quantitative tightening will likely be gradual with plenty of advance notice.

Keeping Reserves “Ample” Is the Key to Balance Sheet Normalization

The Fed intends to shrink its balance sheet to a level so that reserve balances are “somewhat above the level judged consistent with ample reserves.”

To support economic growth, the Fed buys government securities from banks on the open market and hands them new money to lend to individuals and businesses. Whatever is not lent out stays on the Fed’s balance sheet as reserves. Too many reserves, however, can lead to inflation, irrational behaviors, and asset bubbles. After nursing the economy back to health through QE, the Fed needs to “normalize” its balance sheet by draining reserves, via quantitative tightening, to a “minimum level of ample reserves,” where the Fed retains the flexibility to “implement monetary policy efficiently and effectively.” The Fed codified this normalization framework in 2019 as the ample reserves regime.4

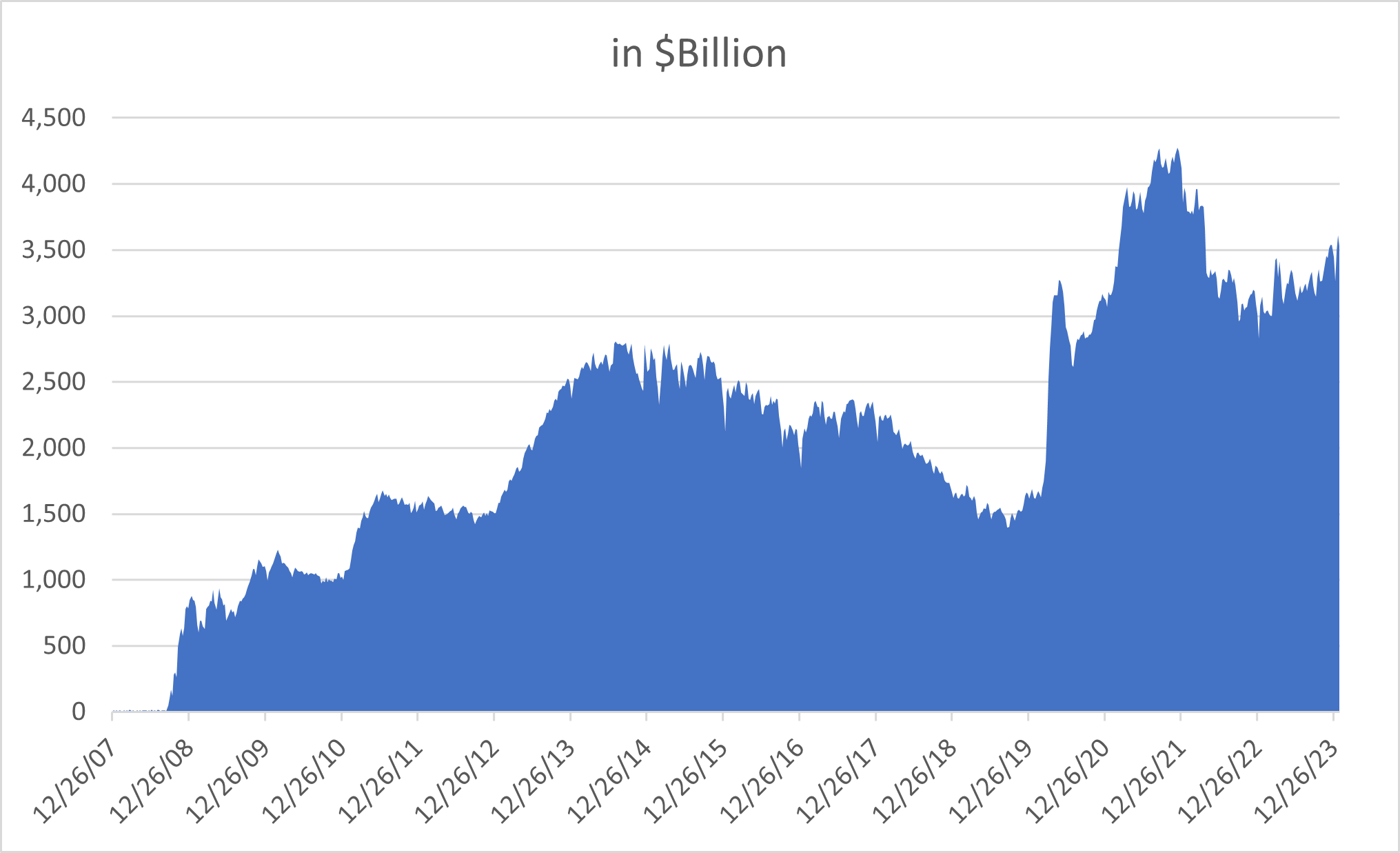

Figure 1. Reserve Balances with Federal Reserve Banks

Source: FRED (Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis)

The ample reserves regime means that the Fed does not want to drain all of the QE reserves. Post-GFC, reserves grew from virtually nothing to $2.1 trillion through July 2013. Subsequent QT drained only $700 billion. Covid-related QE created $2.5 trillion reserves between March 2020 and November 2021. As of January 24, 2024, reserves stood at $3.5 trillion for a total reduction of $683 billion. The lowest reserves in the current cycle were $2.8 trillion in January 2023, two months before the regional banking crisis that caused banks to build up reserves as a defensive measure.

Repo Ruckus Shows It’s Not Easy to Find the Right Level of Ample Reserves

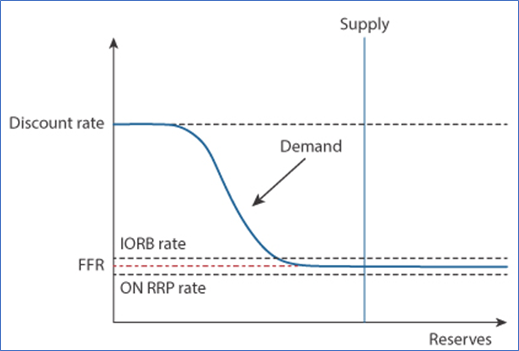

Notwithstanding market anticipation, Fed officials must first contend with where the minimum level of ample reserves lies. Official literature explains it as a level at which the Fed’s supply curve of reserves intercepts banks’ demand curve. When reserves are plentiful, the Fed can keep the interbank borrowing rate, the FFR, between its two administered rates, the interest on reserve balance (IORB) rate and the ON RRP rate. When reserves are too few, banks scrambling for funding may be forced to borrow at a rate above the IORB rate, which makes the Fed’s job of managing the FFR more difficult. Figure 2 provides an illustration of the interception and where reserves become scarce (no longer ample) when the demand curve steepens.5

Figure 2. Monetary Policy with Ample Reserve

Source: FRED (Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis)

The illustration shows that the Fed does not have a working definition or a calculating formula for a minimum level. It can only be observed by monitoring short-term interest rate differentials. When banks are reluctant to lend reserves out at higher repo rates than the IORB rate at the Fed, reserves are said to be no longer ample.

The infamous 2019 “repo ruckus” that saw government repo rates skyrocketing to 10% from 2% was partially attributed to reserve scarcity after the Fed drained $700 billion of reserves to end QE. At $1.4 trillion on September 18, 2019, reserves were higher than the $500 billion to $1 trillion range of estimates of ample reserves based on surveys of senor bank executives.6 This episode had a profound impact on the market’s collective awareness of liquidity crunch and financial market stability from reserve scarcity.

The Fed May Not Be in a Hurry to End Quantitative Tightening

The market expects more details from future FOMC meetings on how the Fed will go about slowing QT, including a timetable to scale back monthly runoffs. Some participants anticipate “tapering” to take place as early as March and end before September of 2024. Using history as a guide and barring unforeseen circumstances, the process may take longer than anticipated.

If reserves at $1.4 trillion back in September 2019 were too scarce, and at $2.8 trillion in January 2023 did not raise alarms at the Fed, the final number may lie somewhere in between. If we further assume the $95 billion monthly securities runoffs fully translate into reserve reduction, the balance will take 15 months to fall to a hypothetical minimum level of $2.0 trillion, or April 2025. If the Fed starts with tapering, the process could take longer.

This is a simple arithmetic exercise that may not prove useful in the real world. A level considered ample at one time in calmer market conditions may be scarce at another time in more volatile markets, especially when risks are on the market’s mind. For example, reserves stopped declining and started climbing in March 2023 despite ongoing balance sheet reduction. It was an indication that bank executives needed more reserves to prepare for higher deposit withdrawals after several regional banks failed. The incident may suggest that the minimum ample reserve level may not be a set dollar figure but a derivative of market sentiment.

The size of the balance sheet and the reserves balance do not always move in a 1-to-1 relationship. Referring to the earlier primer, the balance sheet grows as demand for currency rises without affecting reserves. The Treasury Department account tends to move in the opposite direction from reserves, leaving the balance sheet unchanged. Reduced RRP usage may lead to higher Treasury and reserve balances when investors buy Treasury and corporate securities without affecting the total balance. Thus, movements in other Fed liabilities can complicate the minimum ample reserves projection.

As a Caveat, Signs of Tighter Financial Conditions May Alter the Fed’s Course

Not all signs point to a later end to quantitative tightenting. Many market participants are aware of the spectacular decline in the usage of the RRP facility. Lower RRP balances may be an indication of functioning capital markets, because banks and investment funds are more willing to lend to private parties than parking cash at the Fed. The flip side of the coin is the depletion of excess market liquidity. It may be concerning when decreases coincide with wider yield spreads from private repo counterparties over the RRP to attract cash investors, an indication of tight financial conditions.

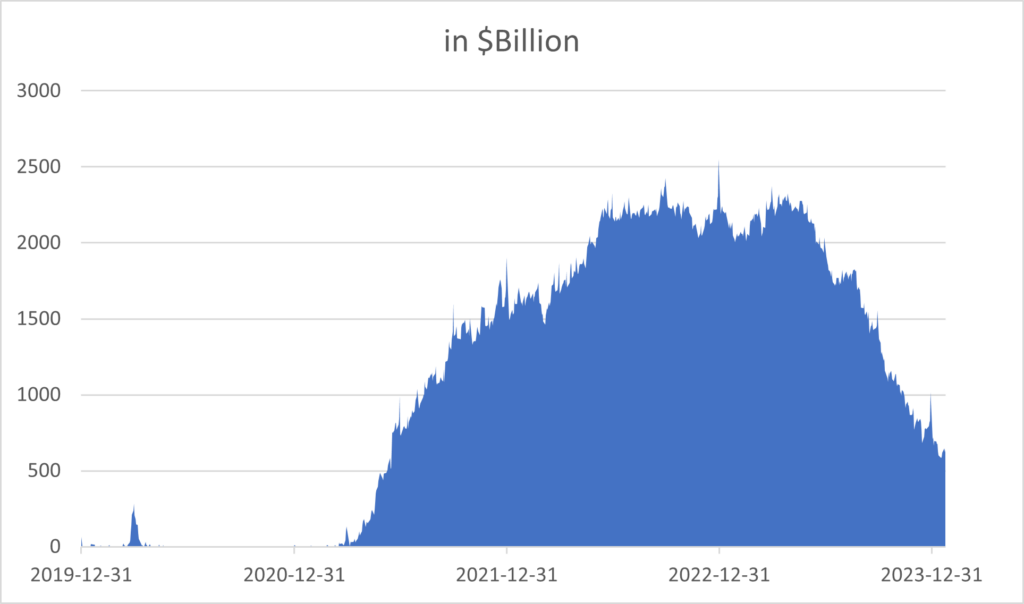

Figure 3 shows that RRP balances have been on a steady decline since early 2023, reflecting cash flowing to higher yielding instruments, and more recently to longer-term investments in anticipation of interest rate cuts. The December FOMC minutes noted the decline “largely reflected portfolio shifts by money market mutual funds toward higher-yielding investments, including Treasury bills and private-market repo.”7 A comparison of balances between April 24, 2023, and January 14, 2024, shows an average weekly decline of $43 billion in RRP balances (excluding foreign official and international accounts). If the current trend continues, the facility could fall from $639 billion on January 24 to zero in 15 weeks, or in early May 2024.

Figure 3. Other (Non-Foreign Official and International Accounts) RRP Balance

Source: FRED (Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis)

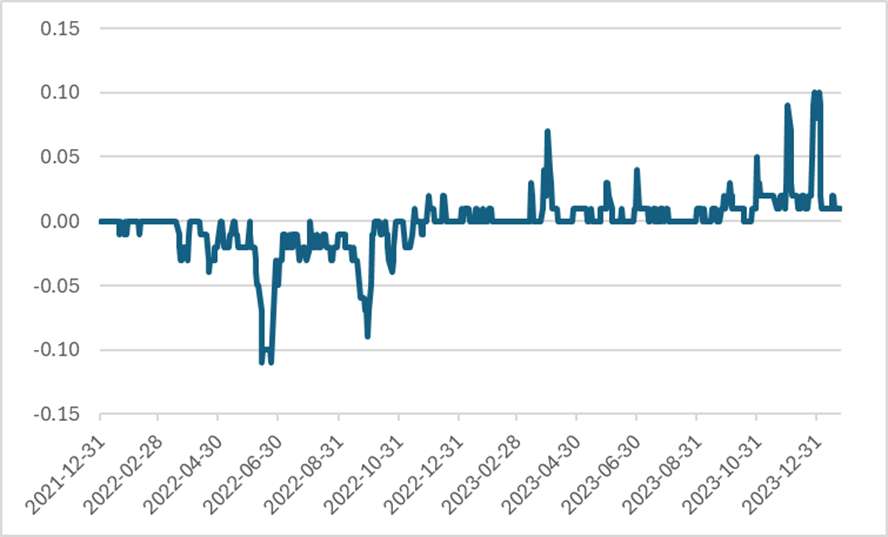

Tighter financial conditions can be observed in the spread between the secured overnight financing rate (SOFR) and the RRP rate, which turned positive from negative several months after the Fed started hiking rates. SOFR is a broad measure of the private sector’s overnight cost of borrowing collateralized by Treasury securities. The RRP rate, on the other hand, is an administered fixed rate to all eligible counterparties. A higher SOFR to RRP spread reflects higher funding costs to broker-dealers in the overnight market, tighter financial conditions, and reduced market liquidity. Excluding quarter-end dates, the spread was within 1 to 2 basis points for most of 2023 but spiked higher more frequently since December 2023.

Figure 4. SOFR to RRP Rate Spread

Source: FRED (Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis)

Figures 3 and 4 provide a reality check against a numerical target for the minimum level of ample reserves, meaning that, despite high reserve balances, the Fed may pause or end QT to improve market liquidity and financial stability if conditions require.

What Does All of This Mean to Cash Investors?

Market participants’ interest in how the Fed will guide QT to an end may have less to do with a marginally more accommodating monetary policy than potential disruptions to market liquidity and stability. Since the Fed formally adopted the ample reserves regime in 2019, this will be the first time we get to witness a banking system with reserves no longer “abundant” but merely “ample,” or even “scarce” if the Fed lets the runoffs go on for too long. A question to consider: Will we have another repo ruckus or something worse?

We believe the recent FOMC chatter is related to how the Fed will guide the market on its decision process before the go-date. It may opt for a tapering strategy to roll back runoffs over several months. We do not expect the Fed to rush this process.

We used a few scenarios to show that deciding on when to end QT is part science and part art. While there is strong evidence that reserves are not scarce and may not be for some time, other market developments, such as concerns with bank loans or dealer funding capacity, may short-circuit the Fed’s timetable. We saw it happen in March 2023 when the Fed started a new emergency funding facility, the banking term funding program (BTFP), to cope with the regional bank crisis which reversed some of its quantitative tightening efforts. This example should allay institutional cash investors’ concerns with QT-induced liquidity shortage.

Another reason not to lose sleep over the timing of QT’s end is that the Fed has tools to improve its ability in implementing monetary policy and financial stability. It unveiled the standing repo facility in July 2021 that can lend cash to eligible banks and primary dealers collateralized with government securities. If all else fails, the Fed can restart QE and create more reserves through Treasury purchases. Stated differently, even if the Fed gets it “wrong” and causes liquidity shortfalls, their negative effects will likely be mild and short-lived.

This does not mean that investors shouldn’t be mindful of recent developments in reserves and repo markets. As we suggested in this whitepaper four years ago, ample reserves do not mean every part of the short-term debt market is liquid. Liquidity can dry up unexpectedly. In the backdrop of larger federal deficits and more stringent bank regulations, cash investors should consider diversifying the sources of their portfolios’ liquidity to include overnight vehicles, such as government money market funds and government repos, as well as high-quality government and corporate securities with laddered maturities.

1 “Federal Reserve Balance Sheet: Factors Affecting Reserve Balances – HJ.4.1,” Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, January 24, 2024, www.federalreserve.gov/releases/h41/current/.

2Bin Wei, “How Many Rate Hikes Does Quantitative Tightening Equal?” Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta’s Policy Hub, No. 11-222, July 2022, www.wsj.com/economy/central-banking/fed-tiptoes-toward-dialing-back-key-channel-of-monetary-tightening-55127982?mod=djemRTE_h.

3See Minutes of the Federal Open Market Committee, December 12-13, 2023, www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/fomcminutes20231213.htm.

4“Principles for Reducing the Size of the Federal Reserve’s Balance Sheet,” Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, January 26, 2022, www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/pressreleases/monetary20220126c.htm.

5Jane Ihrig and Scott A. Wolla, “The Fed’s New Monetary Policy Tools,” Page One Economics: Economic Research, Federal Reserve Bank of St. St Louis, August 2020, research.stlouisfed.org/publications/page1-econ/2020/08/03/the-feds-new-monetary-policy-tools.

6Lance Pan, Repo Ruckus Reveals Hidden Issues in Liquidity Markets, Capital advisors Group, October 18, 2019, www.capitaladvisors.com/research/repo-ruckus-reveals-hidden-issues-in-liquidity-markets/.

7See Minutes of the Federal Open Market Committee, December 12-13, 2023, www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/fomcminutes20231213.htm.