Repo Ruckus Reveals Hidden Issues in Liquidity Markets

Abstract

Rather than dismissing September’s repo turbulence as stemming from idiosyncratic events easily rectified by the Fed, we think that the event reveals broader vulnerabilities within the hidden plumbing of our financial system. Although not all institutional cash portfolios directly use repo, this squeeze should concern us all. We don’t think there is a shortage of reserves per se, but we do believe that they have been rendered immobile by various financial regulations. Banks’ reluctance to act as intermediate liquidity providers is further complicated by higher needs from non-bank financial borrowers and the rising influence of MMFs. Before a long-term solution can be found, institutional cash investors should reassess the liquidity structure in their cash portfolios and consider strategies to fund themselves in unforeseen situations.

Introduction

If a lone tree in a remote forest was struck by lightning and caught fire, but no one was around to witness it, was it really on fire? What if a second tree also caught fire before the emergency crew put it out? Is this cause enough to worry about a forest fire?

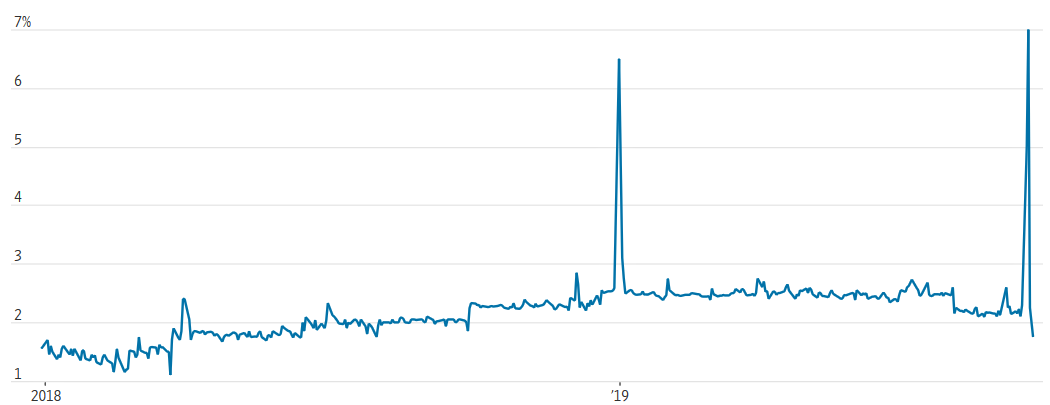

On the otherwise uneventful mornings of September 16 and 17, an unobtrusive part of the financial markets called repurchase agreements—colloquially known as the repo market—experienced these brush fires of sort when overnight interest rates briefly spiked as high as 10% from a starting point of around 2%. In response, the emergency crew, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, sprang into action and injected liquidity into the financial system on multiple days to lower rates and calm market nerves.

The Fed’s decisive liquidity injection notwithstanding, one cannot help but wonder how the mundane repo market, often referred to as the “plumbing” of the financial system, seized up without warning. Was it an isolated event or a symptom of something deeper and more troubling? The air of confidence exuded from Fed officials that the situation was easily contained contrasts with their cautionary measure of keeping the temporary liquidity option open beyond September quarter-end. How should institutional cash investors process and understand this market “anomaly” and be prepared for future unexpected liquidity events?

This paper will provide a brief recap of the September repo event and the relevant factors that caught the market off guard. We published a short blog on September 23 on this topic, and here, we plan to dig a little deeper to help chart a course of action to manage institutional cash portfolios.

A Brief Word on the Repo Ruckus

Financial markets in the US were relatively calm on Monday, September 16, with no meaningful news headlines other than the drone attacks on Saudi oil facilities over the weekend. The short-term funding markets, however, were in turmoil. While most trades were conducted at levels close to the top of the fed funds rate (FFR, at 2.25%), some dealers had to scramble to access funding, paying overnight rates as high as 8%1. Overnight repo rates often experience volatility on certain dates such as quarter-end and tax time, but the magnitude of the surge in rates has been unseen since the financial crisis a decade earlier.

To the disbelief of market participants who dismissed the Monday episode as a temporary abnormality, funding markets did not return to normal the next day. Instead, repo rates surged further at the open Tuesday, briefly topping 10%. The increase caused the benchmark secured overnight funding rate (SOFR) to more than double and took other short-term benchmark rates higher, including the effective fed funds rate (EFFR) and commercial paper rates2. In response, the Federal Reserve announced it would re-start open market operations (OMOs), the first such action in more than a decade, by injecting $75 billion of cash through repo transactions with primary dealers at a fixed rate of 2.10%3.

The Fed’s OMO program experienced a difficult start due to timing and technical issues, but eventually succeeded in providing $53 billion of liquidity to the system on Tuesday. Coincidentally, this happened to be the day before the Fed concluded its Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meeting and lowered the target FFR to a range of 1.75-2.00%.

The Fed continued to support the repo market by extending OMOs for the next two days at the new floor rate of 1.80%. On September 20, it offered three additional 14-day term repo operations of $30 billion each and promised to extend the $75 billion daily program to October 10, 2019. The sizes of both programs were later increased to $60 billion and $100 billion, respectively.

The Fed’s actions resulted in improved liquidity and lower rates in the repo market. Since the intervention, the secured overnight funding rate (SOFR), the broad index of government repo rates, has been generally below the top of the FFR range (2.00%).

Figure 1: History of Overnight Repo Rate

Source: Refinitive and Wall Street Journal (John Sindreu, Rest Easy: The Fed Isn’t Losing Control of Money Markets, WSJ, September 20, 2019)

Probable Direct Causes for the Spikes

By now, it is generally agreed that the small fire in the repo market was caused by a combination of factors including corporate tax payments, large Treasury issuances and constrained deal balance sheets.

On the supply side, September corporate tax payments drained about $83 billion from the system as funds flowed from bank reserves to the Treasury’s account. On the demand side, two Treasury auctions from the previous day resulted in $54 billion that bond dealers need to borrow against on that day. A Wall Street Bond Research team estimated the day’s extra funding needs to be $137-161 billion4.

When viewed against the total size of the government repo market of $2.1 trillion (as of August 9, 2019, FRBNY data), the sudden rise in borrowing costs to near double digits due to roughly $150 billion of extra funding needs is rather stunning. It’s also interesting to also consider why the market turbulence on Monday was not contained until the next day following the Fed’s hurried late-day intervention.

Is the Lack of Bank Reserves the Bogeyman?

Some market commentators were quick to point to reduced bank reserves as the culprit behind the shortage of liquidity in the repo market. This may be true to some point, but that’s not a complete picture.

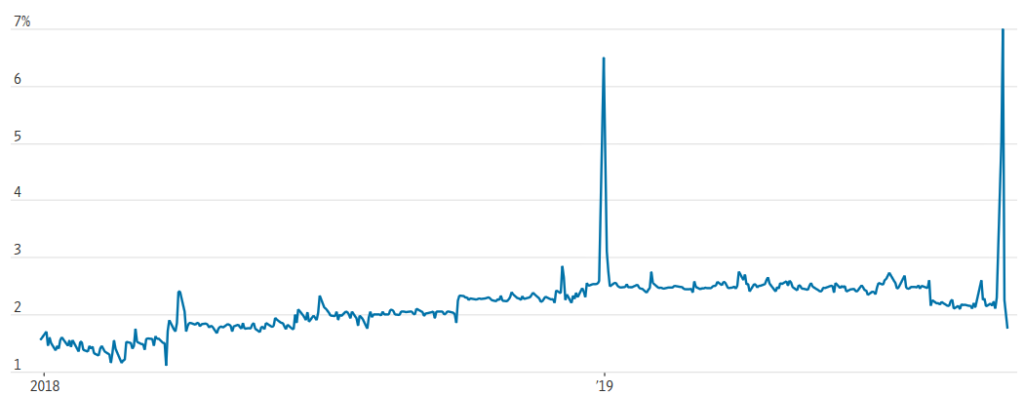

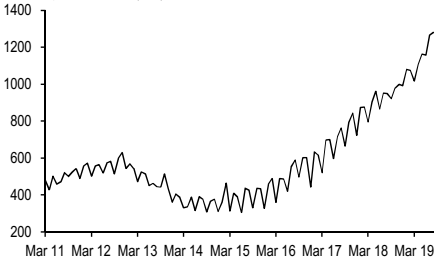

Several rounds of asset purchases by the Fed in efforts to support the economic recovery caused its balance sheet to expand from $922 million at the end of 2007 to $4.5 trillion in January 2015. Starting in October 2017, the Fed began gradually reducing reinvestments of maturing Treasury and mortgage securities it owned. This reduced the balance sheet to $3.8 trillion by July 2019, when it halted further “tapering” of reinvestments. As a result, total deposits on the Fed’s balance sheet went from $40 billion at the end of 2007 to $2.70 trillion in January 2015 and eventually to $1.39 trillion on September 18, 20195.

Figure 2: Reserve Balance at the Federal Reserve

Source: Federal Reserve

The fact that reserves were nearly halved from their highest mark seems to support the claim of reserve scarcity leading to a liquidity shortage. However, in a “fractional reserve” banking system6, reserves are separated into required and excess reserves. Required reserves currently account for $200 billion, which leaves more than 86% of the $1.39 trillion as excess reserves, i.e. excess liquidity.

In recent years, the Fed had publicly expressed its intention to retain “abundant,” then “ample” reserves to maintain balance sheet flexibility to manage unforeseen liquidity needs. Said differently, it did not want to return excess reserves to zero, but rather leave some cushion to manage events like the September 17-18 repo needs.

Based on a Fed September 2018 survey of senior financial officers from 30 domestic and 21 foreign banks, between $650 billion and $900 billion of reserve balances would be the “lowest comfortable level” to address the Fed’s “ample” reserve concern7. Private surveys and estimates from bank experts at that time generally regarded $500 billion to $1 trillion as a prudent level before the Fed pauses on balance sheet reduction.

The current reserve balance of $1.38 trillion is apparently far above those estimates, so were the Fed and market experts off mark on what constitutes enough liquidity? It may be helpful to point out that the repo market is parallel to banking reserves as institutional liquidity, with some but not all participants having access to both sides. We think bank reserves may be wrongfully blamed for liquidity shortage, although reserves certainly play a part, as we will address later.

New Reckoning on Liquidity in the Post-crisis Financial System

Instead of dismissing September’s repo turbulence as an untimely confluence of unrelated events which was easily dealt with by the Fed, we see it as a warning of how vulnerable and fragile the plumbing of the financial system has become. The deep-rooted causes may be due to structural, or systemic, changes to the post-crisis financial system following years of stricter regulations and changed operating models.

The undesirable side effect of safer banks: Relentless financial reforms in the US and abroad since the financial crisis have resulted in generally stronger banks, specifically from a capitalization and liquidity profile perspective. The positive results, however, came at the expense of credit availability and liquidity to the general market. Stricter leverage requirements, known as the supplementary leverage ratio (SLR), have made low-risk liquid assets such as government-backed repos less desirable to hold as they require as much offsetting capital as more profitable, less liquid corporate loans. Likewise, liquidity requirements such as the liquidity coverage ratio (LCR) require banks to keep commensurate liquid assets such as Treasury securities and bank reserves on hand against potential deposit runoffs. As a result, banks are more reluctant to support the repo market in a liquidity shortage, even when it might be economically beneficial to do so8.

A smaller dealer network with stretched balance sheets: Casualties from the financial crisis, stringent regulations, better profit margins elsewhere and direct trading mechanisms with the Treasury have reduced the number of primary dealers trading directly with the Fed on government securities by nearly half, from 46 a decade ago to 24 today. We often hear about “balance sheet capacity” issues when the dealers hold fewer securities on their balance sheets as inventory. Over the years, the Fed’s efforts to attract more securities firms as primary dealers to diversify its dealer network have not been fruitful9. The liquidity markets are thus left with a small group of intermediaries to funnel liquidity on ever larger deficit-induced government debt offerings. What happened to the repo market last month may be a preview of more squeezes down the road, especially at quarter- and year-ends.

Funding challenges at non-bank financial borrowers: Stresses in the repo market played a role in the near collapse of the financial system in 2008. While the banking system in general appears to be safe and sound today, non-bank financial entities are playing a larger role in pursuing risk opportunities shunned by banks. Without access to deposits and reserves, they must access other funding channels, including the repo market for short-term funding. Hedge funds, mortgage REITs, non-primary dealers and other “leveraged” borrowers routinely use this market to finance bond inventories or to speculate on price differences. Smaller dealers may have their own difficulties in balance sheet capacity and liquidity means. If the market experiences signs of liquidity shortages, borrowing costs for non-bank financial borrowers and smaller dealers could skyrocket to unseen levels10,11.

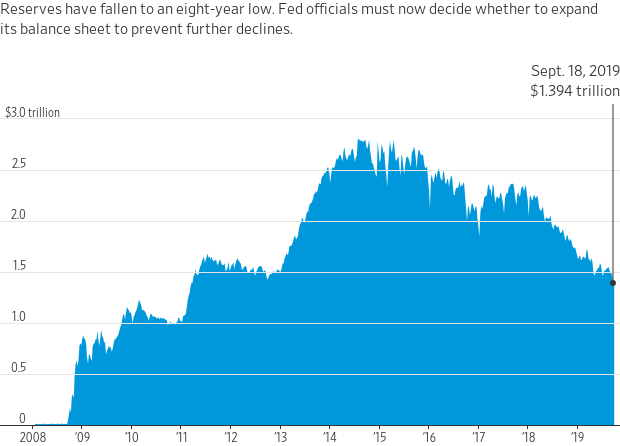

Money market funds as the new (big) kid on the block12: Another relevant factor is the role of money market funds (MMFs) in the liquidity dynamics of repo markets. Repos have been liquidity tools for MMFs for decades, but the MMF regulatory reform in 2016 resulted in massive asset shifts from prime funds that primarily hold commercial paper and credit instruments to government funds that rely heavily on government repos. Since 2017, the Fixed Income Clearing Corporation (FICC) started to allow MMFs in its sponsored repo program as indirect cash lenders to the dealer network . As of August 2019, MMFs finance $1.28 trillion of dealer collateral, or more than half of the daily volume of the entire repo market. This new phenomenon in repo market dynamics turns out to be a double-edged sword: MMFs represent a fresh and large source of liquidity for repo borrowers, while also exposing them to unexpected institutional shareholder redemptions. For example, $30 billion of the estimated $83 billion in corporate tax payments on September 16 came out of MMFs. While these outflows may not have been the cause for stress, they might have added to the surprise where least expected.

Figure 3: Dealer Repo with MMFs ($bn)

Source: Crane Data, J.P. Morgan

Solutions to Improve Repo Market Conditions

As a temporary measure to relieve liquidity stresses, the Federal Reserve has been conducting daily and term repos with primary dealers through temporary OMOs. At the press conference following the FOMC meeting, Fed Chair Jerome Powell affirmed that the Fed will not hesitate to use “tools” to address pressures in the money markets. The market widely expects the Fed to reintroduce these measures around key calendars as temporary means until some permanent solutions are put in place. Other likely solutions discussed by the market include:

Start the standby repo facility: The Fed floated a permanent standby repo facility (SRF) idea a few months ago to help banks convert Treasury holdings into cash when liquidity needs arise. If the current reverse repo facility (RRP) is in place for the Fed to drain liquidity by receiving cash and lending out securities, the SRF acts in the opposite direction to add liquidity by taking in securities and handing out cash. Unlike OMOs, which are temporary and face only broker-dealers, the SRF will be a permanent facility facing banks. It is viewed as an alternative way to add liquidity without adding reserves. It is estimated that SRF may take several months to launch as the Fed needs to decide on the size, rate level and the names on the list of counterparties.

Grow the Fed balance sheet: If $1.6 trillion of reserves seem insufficient to support market liquidity, a logical solution would be for the Fed to add reserves by buying Treasury securities. After the Fed halted the reduction of its balance sheet last July, the amount of currency in circulation and the Treasury’s general account grew in size, and reserves declined steadily. In order to keep reserves at the current level or add to reserves, the Fed will need to buy more securities. The Fed anticipates achieving “organic growth” of its balance sheet in the coming months but to exert a meaningful impact on system liquidity, the Fed will need to purchase more Treasuries than needed to replenish reserves. Such an action would also be considered “quantitative easing,” a result which the Fed may not have intended unless economic conditions warranted.

Provide regulatory relief: Since much of the “excess” reserves are locked up in the banking system by regulatory requirements, less stringent rules, such as excluding government securities from leverage calculations, including repos with the Fed, may help to improve liquidity. Expanding the counterparty list in the Fed’s current liquidity program should also help. The FDIC is close to a decision to eliminate margin requirements in intracompany swap agreements, potentially freeing up $40 billion in liquidity14. In general, we think rolling back regulations on Wall Street in an election year may be politically unappetizing.

Reduce interest rate on reserves: Another short-term fix is to lower the interest rate the Fed pays on excess reserves (IOER). Along with a 25bps cut to the FFR, the Fed lowered the IOER by 30 bps to 1.80%, or 20 bps below the top of the 1.75-2.00% FFR range. This move was intended to encourage banks to lend out their reserves and to bring the effective FFR down to within the target range. The move does not address the imbalance in the repo market directly, but it helps to lower the FFR and through which, other short-term borrowing rates.

Lessons for Institutional Cash Investors

Not all corporate and institutional liquidity portfolios use repos as direct cash investments, but the seemingly isolated liquidity squeeze should concern us all. Contrary to the school of thought that liquidity dislocation creates extra income opportunities for cash investors, we need to be mindful of the risk to our own portfolios and potential loss of access to liquidity.

Plentiful liquidity may be only part of the story: We have seen that despite over $1 trillion of reserves and twice as much in overnight repos, a mere estimated $150 billion in extra funding nearly brought down the entire system and did not right itself without the Fed’s assistance. The system may be swimming with liquidity, but it is not flowing freely to the parts of the market that need it the most. How do we budget our liquidity needs relative to resources so we can avoid being caught in a downward spiral?

Liquidity can dry up at any time: Unlike previous instances when repos rates spiked above the Fed’s target range at quarter-ends or in response to credit events, this episode happened mid-month without major market moving news. The traditional calendar effect remains in place, but we need to add additional safeguards to our liquidity management to be prepared for the unpredictable on any given day.

The calendar effect may be more pronounced: Market experts agree that if what happened in September was a symptom of the liquidity mechanism functioning at full capacity, stresses around quarter-ends and year-ends may become more challenging. While the Fed is expected to inject liquidity through OMOs, the liquidity may still have trouble getting to the right places. Liquidity investors should build their own strategies around key dates.

MMFs will be scrutinized as a reliable source of liquidity: As their role as liquidity providers to the funding market grew through the FICC’s sponsored repo program, government MMFs firmly established themselves as systemically important to the stability of the short-term debt markets, a role previously played by prime funds. While this access benefits both the fund industry and the dealer community, their presence also subjects the repo market to adverse effects of large unexpected shareholder activities. As fund shareholders, institutional investors should be aware of the shortfalls of shared liquidity in a commingled liquidity vehicle. In addition, history shows that unexpected changes in one large fund could have liquidity consequences in other funds. Contingent liquidity planning may include other liquid assets such as deposits and separately managed accounts (SMAs).

Be prepared for the long haul: The fact that the Fed upsized its temporary OMO repos and introduced term repo facilities indicates that the issue in the repo market is structural, and as such, it will take time to resolve. Several measures are working, but a permanent solution may be some time away. We expect liquidity crunches to become worse as large fiscal deficits bring more government securities to be financed by repos. An appreciating dollar invites foreign borrowers to chase down dollar assets and deplete market liquidity. The events of September may occur with more frequency and regularity. Investors should be prepared for this reality and perhaps demand a permanent risk premium when they lend cash to governments, banks, and commercial paper issuers.

Conclusion

Although Bill Dudley, the former New York Fed President, said in a Bloomberg op-ed that the spike in repo rates “is not a harbinger of deeper market problems or a larger crisis”15, we think liquidity investors are rightfully concerned. A small spark of roughly $150 billion in funding shortage set on fire a few trees in the $2.4 trillion repo forest. What could come next? The Federal Reserve eventually brought the situation under control, but its slow response and the difficult start were indications that the central bank was also caught off guard. While liquidity remains plentiful and market sentiment is sanguine, we should maintain our skepticism of the soundness in the “plumbing” of our financial system.

Rather than relegating the causes of the spike in repo rates to a one-off event from coincidental factors, we think it is a demonstration of how little flexibility remains in our funding markets. We think reserves are not in shortage per se but have been rendered immobile by various financial regulations. Banks’ reluctance to act as intermediate liquidity providers is further complicated by higher liquidity needs from non-bank financial borrowers and the rising influence of MMFs.

While a long-term solution to return the repo market to normal remains months away, institutional cash investors should take this market event as an opportunity to reassess the liquidity structure in their cash portfolios and consider strategies to fund themselves in unforeseen situations. Some may view cash investors as beneficiaries of a stressed repo market as a result of higher rates, however, we should also consider the tale of a shy mythical creature who runs away when you call out its name—liquidity.

DOWNLOAD FULL REPORT

Our research is for personal, non-commercial use only. You may not copy, distribute or modify content contained on this Website without prior written authorization from Capital Advisors Group. By viewing this Website and/or downloading its content, you agree to the Terms of Use.

1Blake Gwinn, US funding: Anatomy of a breakdown, NetWest Markets, Rates, United States, September 20, 2019.

2Gwinn, US Funding.

3See Federal Reserve Bank of New York’ Statement regarding repurchase operations on September 17, 2019 and following days. https://www.newyorkfed.org/markets/opolicy/operating_policy_190917

4Steve Kang, Short-end notes: And then a hero comes along, Citi Research: Rates, September 20, 2019.

5From the FRED database at the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. https://fred.stlouisfed.org/categories/123

6For a primer on fractional reserve banking, refer to What is fractional reserve banking? By Julia Kagan on Investopedia, updated September 12, 2019. https://www.investopedia.com/terms/f/fractionalreservebanking.asp

7Thomas Keating, Francis Martinez, et al. FEDS notes: Estimating system demand for reserve balances using the 2018 senior financial officer survey, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, April 9, 2019.

8Alex Roever, Teresa C Ho, et al. Repo: What just happened? J.P.Morgan North America Fixed Income Strategy, September 17, 2019.

9Katy Burne, Fed moves to expand pool of primary dealers, the Wall Street, Journal: Markets, November 9, 2016. https://www.wsj.com/articles/fed-moves-to-expand-list-of-primary-dealers-1478725962

10Greg Ip, Reforms have made banks safer but markets more brittle, The Wall Street Journal: Economy | Capital Account, September 25, 2019. https://www.wsj.com/articles/reforms-have-made-banks-safer-but-markets-more-brittle-11569416725

11Daniel Kruger, Big banks loom over Fed repo efforts, The Wall Street Journal: Markets, Updated September 26, 2019. https://www.wsj.com/articles/big-banks-loom-over-fed-repo-efforts-11569490202

12Alex Roever, Teresa C Ho, et al. Repo: What just happened?

13DTCC Connection Staff, FICC is transforming the repo market, April 1, 2019. https://www.dtcc.com/dtcc-connection/articles/2019/april/01/ficc-is-transforming-the-repo-market

14Jesse Hamilton, Wall Street may get $40 billion reprieve from Trump regulators, the Wall Street Journal: Politics. September 16, 2019. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-09-16/wall-street-may-get-40-billion-reprieve-from-trump-regulators

15Bill Dudley, Get a grip. The Fed can handle the repo market, Bloomberg Opinion: Finance, September 20, 2019. https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2019-09-20/how-the-fed-can-handle-the-repo-market

Please click here for disclosure information: Our research is for personal, non-commercial use only. You may not copy, distribute or modify content contained on this Website without prior written authorization from Capital Advisors Group. By viewing this Website and/or downloading its content, you agree to the Terms of Use & Privacy Policy.