The Federal Reserve meets next week, and it will, once again, decide what interest rate the economy needs to get inflation under control while continuing to grow. The aim is to get back to a normal economy. The calculation, however, depends on what your definition of “normal” is and what interest rate we’d have in normal, good, times.

You’d want mild inflation and gross domestic product expanding at just the right speed — not losing steam, not overheating. The interest rate that could keep all those things in balance is called the natural or neutral rate.

“The neutral rate is the Fed’s kinda guiding compass,” said Matthew Paniati, a senior analyst at Capital Advisors Group.

In other words, if you’re trying to sail north, you might have to steer east or west sometimes, what with the currents and the wind, but your compass will help you get back on track. It’s the same for the Federal Reserve.

“For the Fed over the long run, the short-term interest rate might deviate from the neutral rate. But in the long run, that’s what they want to get to,” Paniati said.

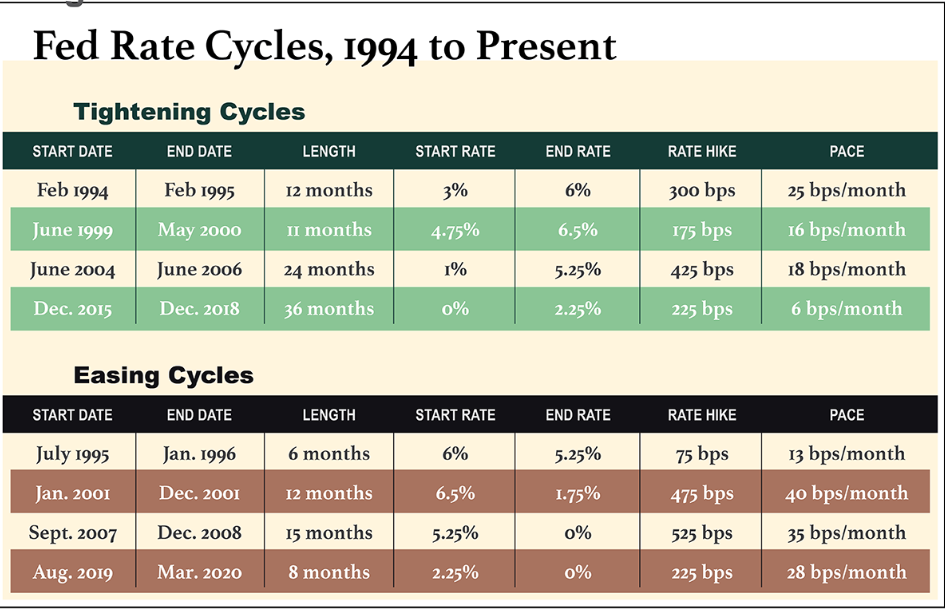

Sometimes things happen — inflation flares up and the Fed has to slow the economy down, or there’s a weak stretch and the Fed has to get the economy moving.

“And when they need to slow the economy down, they raise rates above the natural rate. When they want to speed the economy up, they lower the rate below the natural rate,” said Joseph Gagnon, a senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics.

There is one problem with this North Star, this shining interest rate on a hill: You can’t measure it directly, Gagnon said. It’s theoretical. There’s no simple formula that will spit it out.

“But in hindsight over time, you can see roughly where it is,” he said.

Wait. If you look back in time and the economy was stable, then were the primary interest rates at the time the right ones?

Maybe, according to David Rogal, a fixed-income portfolio manager at BlackRock. “Because the neutral rate is not observable, the error bands for these models are very wide,” he said.

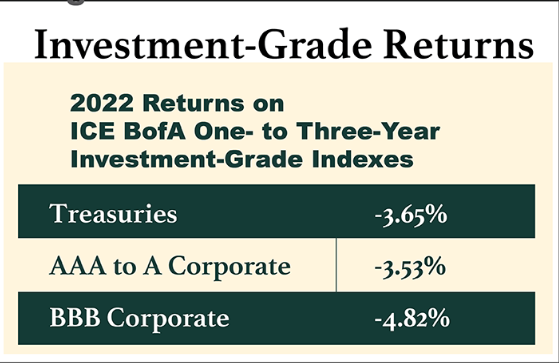

Right now, the Fed believes the neutral interest rate is 2.5%, a lot lower than the 5.5% it’s currently using as the standard. So one day when inflation is all fixed, the idea is we’ll get back down to 2.5%, which would affect new mortgages and car loans and credit cards.

“But I think what you’re hearing from the Fed communications is there’s less certainty about that,” Rogal said.

The mystical Goldilocks neutral interest rate can change depending on a lot of factors — population growth, productivity, federal spending. And it may be changing now.

“I think there’s a lot of good evidence that it’s rising,” said Paniati with Capital Advisors.

For starters, we’ve had high interest rates for more than a year now and the economy has barely bat a lash. No recession, no slowdown, although inflation has cooled.

So maybe the “normal” interest rate of the Fed’s dreams is actually higher than it used to be. But also … maybe not.