Comprehensive Cash Investment Strategies

Abstract

The evolving treasury cash investment landscape and yield disadvantage of bank deposits have prompted many practitioners to look for alternative options for managing their excess cash. We address this topic in a generalized manner, summarizing three major categories of available cash investment vehicles: deposits, pooled assets and direct purchases. The pros and cons of each vehicle type are discussed. Corporate cash investors may benefit from this analysis as they discuss their options internally and with their investment managers.

Introduction

We are closing in on the 10th anniversary of the peak of the global financial crisis marked by the Lehman Brothers bankruptcy and runs on money market funds. Old-timers still remember the exotic species which invaded the previously tranquil meadows of the world of cash such as auction rate securities, extendable asset-backed commercial paper, structured investment vehicles, and collateralized debt obligations, to name just a few. To say that a lot has changed in the corporate cash world is a great understatement.

Our current environment appears much healthier, but it is not without new challenges. We endured an extraordinarily long period of low interest rates that just ended in 2015. The Eurozone debt crisis that sowed the seeds of EU skepticism faded largely into the background, although complications from Brexit remain challenging. The conversion of prime institutional funds to a market-based net asset value (NAV) regime saw the orderly transition of institutional assets to government funds, while similar changes on the European front are just starting. Tougher capital and liquidity requirements and bank resolution reforms in major developed markets made banks more resilient to systemic shocks, although recent regulatory relaxation in the US has slowed this momentum.

Adding to these external factors is the need to find a transitional and/or permanent home for cash infusion from repatriated offshore profits, windfalls from corporate tax relief, and bank deposits that pay stubbornly low interest. With relatively benign market conditions and baseline short-term interest rates hovering around 2%, return on investments is again a notable goal for many organizations in addition to return of investments and liquidity mandates.

With the reset button pressed on so many cash management vehicles and strategies, this is an appropriate time to reintroduce our readers to the comprehensive approach we discussed a few years ago. We discuss these common cash vehicles in a general fashion to allow investors to make their own decisions based on their unique needs and circumstances.

Corporate Cash Over Nearly 50 Years

To some corporate treasury practitioners, cash management options are rather limited – bank deposits and money market funds. This sentiment partially explains why deposit betas – increases in deposit interest in relation to increases in market rates – remain low in the third year of Fed interest rate increases. When prime institutional money market funds (MMFs) were forced to adopt variable NAVs and redemption restrictions in 2016, a predominant shareholder response was to switch into government MMFs rather than looking for other options.

In light of this corporate treasury mindset on alternative cash management opportunities, it may help to provide a historical perspective on how corporations typically managed their cash before the heyday of money market funds.

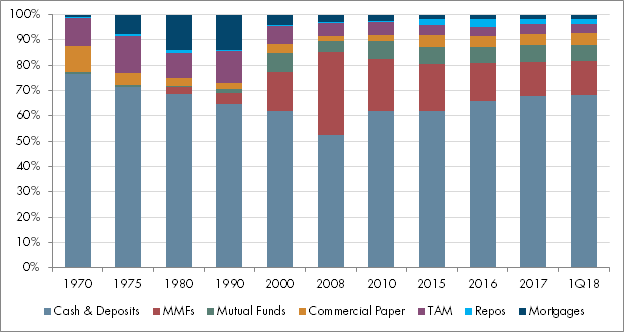

Figure 1 shows financial balance sheets of non-financial businesses on the aggregate in the United States since 1970, according to the Federal Reserve’s Flow of Funds reports. It reveals that while bank deposits always retain prominence on the corporate balance sheet, other types of cash equivalent and marketable security types have changed significantly over time, especially from the 2000’s onwards.

Figure 1: How Liquid Balances at Non-Financial Firms Evolved

Note: Cash & Deposits = Cash + Checking + Time & Savings + Foreign Deposits, TAM = Treasury + Agency/GSE + Muni

Source: Federal Reserve “Flow of Funds of the United States” reports, section L.101, 1970 – 2018.

The graph also shows that, prior to the new millennia, firms held significant portions of their balance sheets in “credit market instruments” that included Treasury and agency securities, commercial paper, municipal bonds, mutual fund shares and mortgages.

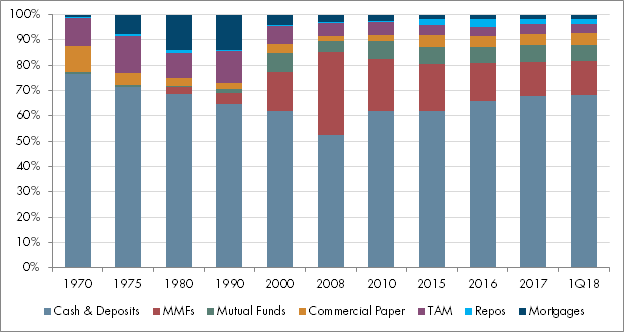

Figure 2: Effect of Bank Mergers since 1994

Note: Cash & Deposits = Cash + Checking + Time & Savings + Foreign Deposits, TAM = Treasury + Agency/GSE + Muni

Repos not depicted here (up 68%, 1010%, 1421%, 1065% and 992% respectively)

Source: Federal Reserve “Flow of Funds of the United States” reports, section L.101, 1970 – 2018.

Figure 2 shows changes since 2008. While the use of MMFs has declined by around 30% as of the first quarter of 2018, investment in most other asset classes expanded, including commercial paper and mutual fund shares which grew by 241% and 160%, respectively. In fact, the growth in security repos was so enormous (at 992% as of 1Q18) that we removed it from this graph to order to avoid dwarfing the other data series.

These illustrations of non-financial business balance sheets indicate a large reshuffling of the use of different cash management vehicles over the last five decades. As one thinks about the total opportunity set in cash investments, it may pay to look outside the proverbial box of deposits and pooled assets such as money market funds. Looking to the past for guidance, cash managers may start considering the possibility of direct purchases of assets in portfolios designed to balance liquidity, risk management and yield.

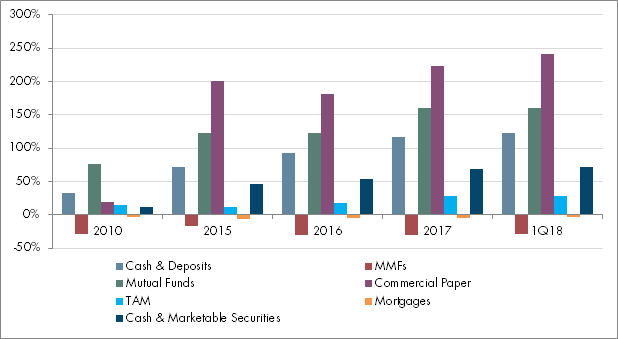

Cash Vehicles At-A-Glance

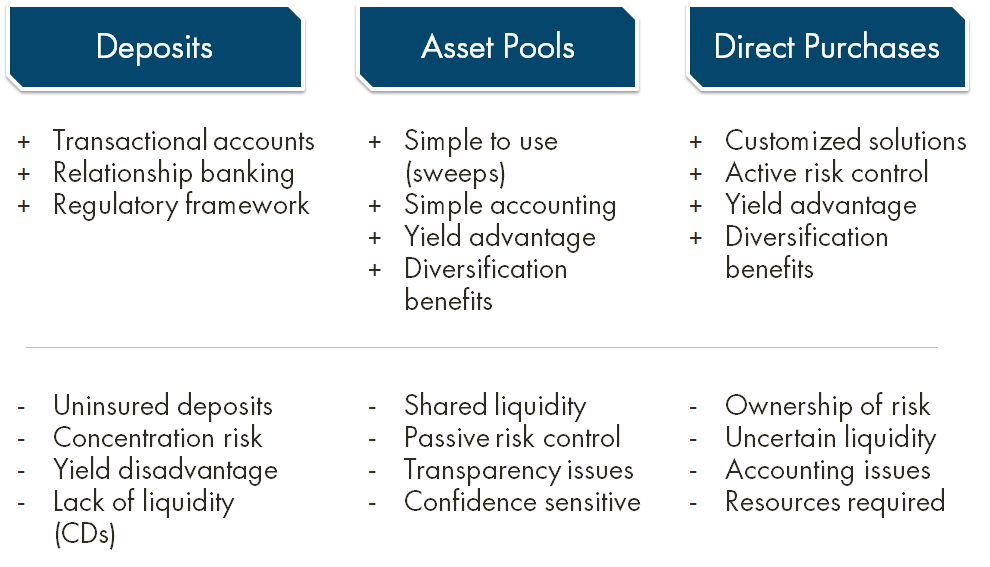

In our opinion, the types of instruments suitable for corporate cash management invariably fall into three categories: deposits, asset pools and direct purchases.

Deposits may include insured and uninsured bank balances. They can be transactional (demand deposit) accounts or time and savings accounts that are issued by U.S. banks, foreign banks, U.S. branches of foreign banks (Yankee deposits) or foreign branches of U.S. banks (offshore deposits).

Asset Pools refer to commingled investments where investors have prorated ownership in professionally managed cash-like instruments. Money market funds are a subset of mutual funds which have a goal of achieving a stable net asset value and providing daily liquidity (which is more challenging for institutional prime funds post reform). Other short-duration asset pools may include ultra-short-term bond mutual funds, local government investment pools, lightly regulated private investment pools (3c-7 funds) and exchange-traded funds.

Direct Purchases are individual securities purchased and held in the name of the investor. Common investments in corporate cash accounts may include security repurchase agreements (repos), U.S. government and agency bills and notes, commercial paper, corporate notes or asset-backed securities. Broker-sold certificates of deposit also may fall into this category. In some instances, investors may choose to hire external managers to look after their investments in separately managed accounts (SMAs).

Figure 3: Cash Vehicles At-A-Glance

Comparing Vehicle Types

Understandably, each of the three types of cash vehicles comes with advantages and disadvantages. Timing of cash needs, risk tolerance and yield expectations, among other factors, may influence the adoption of one or several of these strategies.

1. Deposits: Deposits form the basis of most treasury organizations’ cash strategies. In most cases, demand deposit accounts (DDAs) are the default cash management vehicle because they are readily available and are part of the organization’s overall banking relationship. In addition to the demand feature of deposits, U.S. depositors enjoy a depositor-friendly banking regulatory framework under the supervision of the Federal Reserve Board and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC).

As market interest rates climb, the opportunity cost of leaving balances in non-interest bearing accounts also increases. Banks also have regulatory incentives to encourage savings and term deposits beyond 30 days rather than overnight DDA or money market demand accounts (MMDAs). While “terming out” increases yield potential, depositors sacrifice some liquidity and face early withdrawal penalties.

The main risk in deposits is the credit risk in uninsured deposits. The FDIC deposit guarantees of $250,000 per taxpayer ID per bank often mean that institutional deposits do not enjoy full FDIC coverage. Uninsured deposits are unsecured loans to the issuing banks, so sophisticated credit analysis on bank credit is paramount. Post-crisis bank regulations have improved credit protection for depositors in general, but the new bank resolution framework has only been lightly ‘battle-tested’ in a few Eurozone bank cases, so depositor caution is warranted. In addition, concentration risk to a few relationship banks is a common phenomenon among large corporate depositors, since operational burden increases with the addition of new banks as counterparties.

As we are experiencing today, yields on bank deposits are often less competitive than market rates. Depositors desiring higher yield may sacrifice portfolio liquidity in considering longer fixed-term certificates of deposits.

Also noteworthy, is the fact that many institutions use foreign deposits. While U.S. branches of foreign banks are under the supervision of U.S. regulators, deposits issued in foreign markets or by offshore branches of U.S. banks carry the risk of cross-border transactions and involve different supervisory jurisdictions. Depositors need to assess each situation carefully and not rely on the perceived links of their deposits to foreign governments or the U.S. parents of foreign branches.

2. Asset Pools: In general, the biggest advantage of asset pools is professional management of risk assets, which also brings the benefit of instant risk diversification to individual issuers. Shared liquidity, especially in the case of money market funds, also can be beneficial to investors under normal market conditions. The $1.00 net asset value and daily liquidity of government money market funds offer the convenience of simple accounting and tax reporting. Asset pools may allow managers to purchase securities with better trade execution. Under normal circumstances, yield on assets pools may be higher than bank products because rates are determined by market factors.

On the other hand, the shared nature of pooled investments means that investors also share the downside risk, chief among which is shared liquidity during market disruptions. The vulnerability of money market funds to shareholder runs was illustrated in recent years and remains a contentious issue for further money market fund reforms.

The loss of prime funds’ stable NAVs gave way to the creation of innovative asset pools such as ultrashort bond funds (USBF) and 3c-7 private liquidity funds. While the new vehicles may prove useful in individual cases, they are no longer under the protection of the SEC according to 2a-7 MMF rules. In particular, these portfolios tend to offer less transparency with respect to their portfolio investments. In this regard, shareholders’ risk management role is a passive one in which they can either voice their concerns or vote with their feet.

3. Direct Purchases: As intimidating as they sound to some cash investors, direct purchases represent a back-to-basics approach to cash management. The advantages of direct purchases include the ability to customize investments to suit specific needs, risk tolerances and return expectations of the institutional investor. A separate account solution strengthens the investor’s role in active risk management, which is even more important in today’s environment. A separate account also receives risk diversification benefits similar to pooled assets, but with more precision when stipulated by specific investment guidelines. Because direct purchases are not bound by restrictions imposed on pooled assets, including money market funds, separate account strategies may take advantage of market inefficiencies and produce higher yield opportunities than deposits or pooled vehicles.

Of course, owning securities outright also has its downside. A separate account cements the ownership of risk to cash investors who may be less experienced in investment processes. While such tasks may be delegated to outside managers, investment policy construction, manager selection and portfolio monitoring may involve upfront time and effort. Separate accounts also may require more accurate projections of cash flows to maximize yield potential. Selling securities prior to maturity, even when executed prudently, may result in unwanted gain or loss recognition and create the need for investment accounting entries. The size of the cash portfolio also may determine the applicability of a separate account solution, as smaller lots of securities may be difficult to find.

Figure 4: Comparing Types of Cash Vehicles

Conclusion

The evolving landscape of treasury cash investments may cause anxiety among practitioners looking for ways to house their liquidity portfolios and earn competitive returns, especially when faced with seemingly dwindled selections and influx of cash. We hope our framework of these three types of cash vehicles will facilitate further dialogue internally and with investment managers on the feasibility of each option. We also welcome our readers to reach out to us to discuss specific strategies.

Our research is for personal, non-commercial use only. You may not copy, distribute or modify content contained on this Website without prior written authorization from Capital Advisors Group. By viewing this Website and/or downloading its content, you agree to the Terms of Use.

Please click here for disclosure information: Our research is for personal, non-commercial use only. You may not copy, distribute or modify content contained on this Website without prior written authorization from Capital Advisors Group. By viewing this Website and/or downloading its content, you agree to the Terms of Use & Privacy Policy.