Liquidity in Question – What Do We Do with Prime Money Market Funds?

Abstract

After sudden shareholder redemptions in March stressed money market funds, it became clear that several rounds of reforms since the 2008 crisis have failed to bolster institutional prime money market funds as liquidity vehicles. While extraordinary government measures once again helped to stabilize the market, they should not be recurrent policy decisions. Regulations have reduced the systemic status of prime funds in commercial paper (CP) funding and the overall economy.

Increasing portfolio liquidity or restricting CP allocation may not resolve the drawbacks inherent in prime money market funds due to shared liquidity. Additional reforms are possible, including external and contingent liquidity, shareholder transparency and concentration limits, and repositioning prime funds as ultra-short mutual funds. However, a permanent solution for the funds may take time due to conflicts of interests from the stakeholder groups. Ultimately, we expect institutional cash investors may begin to regard prime funds more as income solutions than as liquidity vehicles.

Introduction

Groundhog Day has been a familiar phrase describing the financial markets’ responses to the Covid-19 pandemic, including prime money market funds (MMFs). For a few days in late March, heavy shareholder redemptions overwhelmed some funds’ abilities to adhere to regulatory requirements. In response, the Federal Reserve swiftly reinstalled several crisis-era liquidity facilities, and Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin went to Congress for permission to guarantee MMFs.

These events were reminiscent of the 2008 financial crisis, when a credit default in one prime fund caused it to break the $1 NAV, precipitating runs on other funds. The Fed reacted by creating several liquidity facilities, and Treasury provided principal guarantees. The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) subsequently enacted two rounds of regulatory reforms to protect the funds against future liquidity events and to remove taxpayer liability. However, judging from what happened this past March, even those measures may not be enough. What really happened and where do we go from here with prime funds?

What Happened to Prime Funds?

According to fund data tracked by iMoneyNet, assets in weekly prime funds peaked on March 10 at $794 billion, with $324 billion in institutional shares and $470 billion in retail shares. Covid-19 caused rapid deterioration of market liquidity in the following week, with total outflows of $64 billion including $52 billion from institutional shareholders. In the weeks that followed, emergency measures by the Federal Reserve and Treasury Department to provide support to both commercial paper issuers and the money fund industry failed to stop the outgoing tide. By the end of the month, outflows from prime funds totaled $147 billion, a 19% reduction. Institutional shares lost $101 billion, or 31% of assets. Prior to the Fed’s intervention, at least two prime funds received liquidity support from their respective sponsors to stay above the 30% weekly liquidity regulatory requirement. Another saw the threshold breached briefly before recovering.

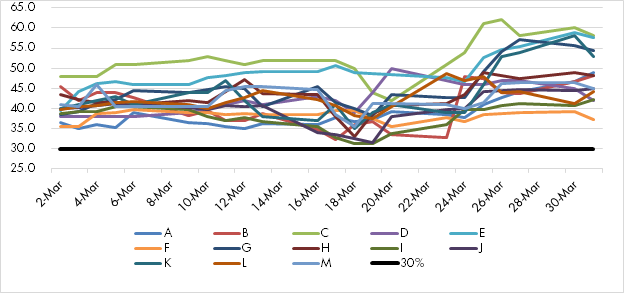

Of the 13 large prime institutional funds tracked by FundIQ®, a money market fund research tool created by Capital Advisors Group, weekly liquidity balances at a few funds came close to the 30% threshold before turning higher. As a group, the average liquidity balance dropped 4.6%, while several individual funds fell more than 10%. In the week of March 12 to March 19, about half of the funds had weekly liquidity balances at 35% or lower.

Figure 1: Weekly Liquid Assets of Prime Funds Tracked by FundIQ®

Source: FundIQ® based on data collected by Crane Data.

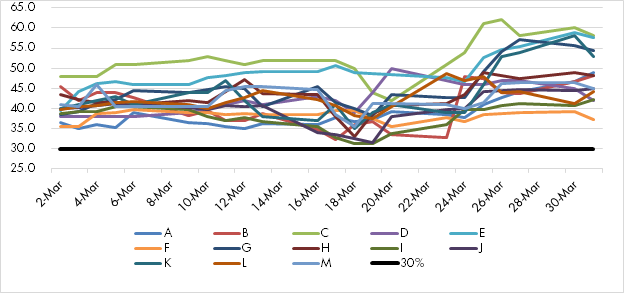

In terms of principal stability, while the NAVs of all the funds were above $1.0000 in early March, all but one dropped below that threshold (Figure 2). The largest drop was 30 bps from $1.0012 to $0.9982. The average drop in NAV was 17 bps.

Figure 2: NAVs of Large Prime MMFs in March 2020

Source: FundIQ® based on data collected by Crane Data.

We should clarify two things at this point. First, as this article is intended for institutional investors, we do not address at length prime funds catered to retail shareholders, which saw lower flow volatility. Second, our recounting of events does not assign blame to asset quality or portfolio management capabilities, as most other asset classes in the financial market suffered an equal fate of evaporated liquidity. What is relevant to us is the reassessment of prime funds as near-cash alternatives in the minds of liquidity investors.

Are Prime Funds “Liquidity” Vehicles?

Before addressing whether or how rules should be modified, let us reflect on what a liquidity vehicle ought to look like.

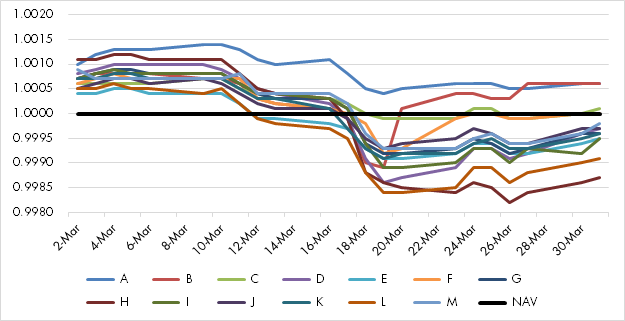

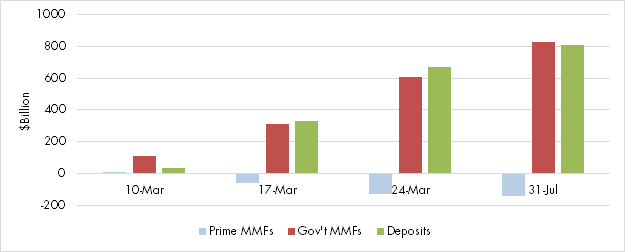

Figure 3: Cumulative Weekly Asset Changes in March 2020

Source: iMoneyNet and Bloomberg data on deposit balances at commercial banks.

No Rainy-Day Fund: If one considers a liquidity vehicle as a source of “rainy day” cash, prime funds apparently did a poor job when it rained. Figure 3 shows the weekly cumulative changes of “liquid” balances in March. As balances in prime funds dropped, greater proportions of cash fled to government MMFs and deposit accounts at commercial banks. What separates prime funds from the other two types of liquidity vehicles? The perceived safety of underlying assets in government funds, and the FDIC guarantees (if only partial) on deposits. We think that initiatives to improve the resilience of prime funds need to be viewed through the lens of why cash investors leave certain “cash” options in a liquidity event.

ALM Challenge in Commingled Vehicles: While it is unreasonable to require prime funds to comply with bank-like liquidity requirements such as the liquidity coverage ratio (LCR), there need to be tighter rules to address shareholder risk. Prime funds have an inherent structural vulnerability because they are a commingled vehicle of shared liquidity with asset and liability management (ALM) challenges. Successive SEC regulations have shortened the regulated weighted average maturity (WAM) of portfolio assets from 120 days to 90 days, and to 60 days since 2016. However, the WAM on the liability side has always been one day. This risk, present in all commingled vehicles, is particularly challenging for prime funds designed to act as sources of liquidity with immediate accessibility.

Shareholder Concentration and Correlation: Fund managers strive to maintain a comfortable liquidity cushion available for immediate withdrawal. The delicate balance of keeping enough cash on hand while still buying longer-term assets to gain yield can be quickly upset by unforeseen market events. An unintended consequence of the 2014 reform that separated institutional from retail shareholders created higher shareholder concentration in the institutional funds. In institutional funds, where dedicated treasury staffs utilize available electronic trading technology, there is a tendency to move quickly to chase yield or avoid risk in response to external shocks. Consolidation of prime funds in recent years also resulted in the same shareholders heavily represented in multiple funds. When a herd starts to retreat, the best spreadsheet trackers and forecasting models may become inadequate, as investors simultaneously unload certain funds at no transaction costs to avoid being caught by redemption fees and gates.

Illiquid Nature of the Short-term Debt Market: It’s a common misconception that if a debt instrument is highly rated with a short maturity, it is considered liquid. The accounting definition of instruments with less than 90-days remaining to maturity as cash and cash equivalents contributes to this confusion. In reality, since instruments including commercial paper (CP) and marketable certificates of deposits (CDs) are largely expected to be held to maturity, the secondary market is generally not large enough to accommodate sell orders from large prime funds, which also tend to have a high concentration of cross-holdings. This is part of the reason the Boston Fed revised eligible asset classes to include deposits (and municipal debt) for the money market fund liquidity facility (MMLF) to become helpful for prime fund liquidity.

How Essential Are Prime Funds to the Financial System and the Economy?

In March, the Federal Reserve acted decisively to backstop liquidity for prime funds and prevent contagion in the short-term debt market. The Treasury Secretary received permission from Congress to guarantee MMF share prices but, as the dark cloud passed, did not implement the guarantee. While we applaud these government actions that addressed the current crisis, we question the wisdom of returning to the “big bazookas” time and again to fix systemic problems. We think it is time for all parties involved to reassess the reliability of prime funds as a liquidity transmission mechanism. The time to fix a problem is not during the crisis, but a crisis should not go to waste.

Prime funds’ role in CP market: We have the SEC and the Fed to thank for the fact that prime funds no longer pose as much systemic risk as they once did. The rationale for emergency government assistance is often one of financial stability, because MMFs are important avenues of funding for businesses, financial institutions, and federal and local governments. Whereas this general characterization remains true for MMFs in general, so much has changed over the years that prime funds—particularly institutional prime funds—may no longer be as useful or essential as they once were.

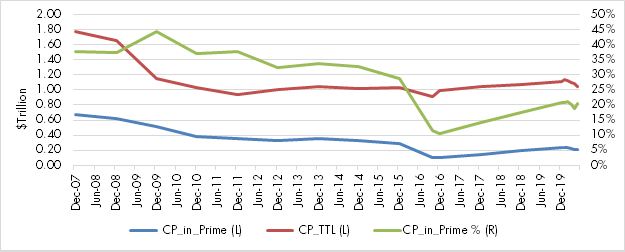

Figure 4: Commercial Paper Held by Prime MMFs (2007 – 2020)

Source: The Federal Reserve Board and Investment Company Institute data

Figure 4 gives us the history of the commercial paper market since the 2008 Great Recession. Total CP outstanding dropped from nearly $2 trillion at the end of 2007 to below $1 trillion in 2011 and ended at around $1 trillion as of May 31, 2020. Total CP held by prime funds, as reported by the Investment Company Institute, dropped from $674 billion in 2007 to $212 billion last May. That is a reduction of 68% on an absolute basis. On a relative basis, about 38% of the CP market was financed by prime purchases in 2007, while the same figure is now nearly halved at 20%.

What this means is that, compared to 62% in 2007, about 80% of the CP market is supported by other investors such as other mutual funds and direct purchases by corporations, municipalities, and asset managers.

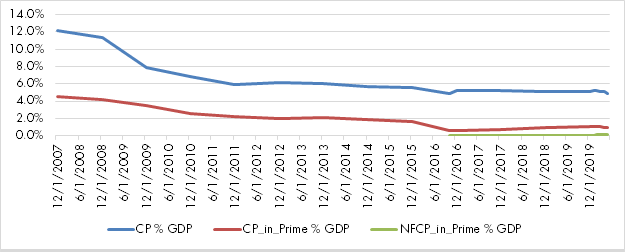

Figure 5: Commercial Paper Held by Prime MMFs as % of US GDP

Source: The Federal Reserve, ICI, and Bureau of Economic Analysis through Bloomberg.

CP funding relative to GDP: The diminished significance of prime funds in the financial system can be further illustrated in relation to the size of the US economy. Figure 5 shows that the, since the Great Recession, the CP market itself has shrunk relative to the GDP, from over 12% then to just under 5% now. CP held by prime funds, which used to represent 4.6% of the economy, now stands at 1%.

“Main Street” funding: In addition, prime funds’ contribution to funding what is known as “Main Street” (non-financial corporations as opposed to Wall Street), hugs the bottom of the curve (NFCP_in_Prime % GDP) in Figure 5. Non-financial CP holdings by prime funds accounted for 0.085% of the GDP in 2007 and 0.157% last May. This distinction is significant because financial borrowers can tap other sources of funding besides CP to support lending and securities businesses through deposits, bonds, asset-backed securities, mortgage backed securities and repurchase agreements. The options for non-financial issuers are more limited. While prime funds no doubt remain an important funding source for the CP market, they are not as essential as they used to be.

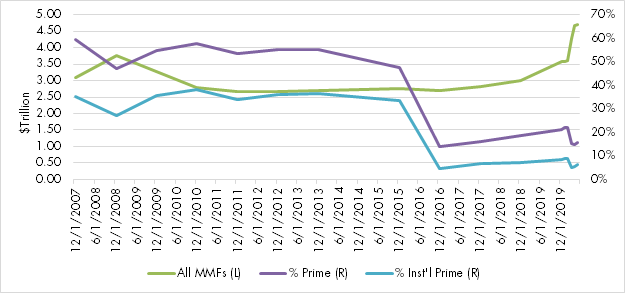

Figure 6: Prime Assets as Shares of Total MMF Assets

Source: iMoneyNet.

Diminished representation within the MMF industry: The analysis is not complete without addressing the liability side of prime funds. MMFs continue to be a popular cash management tool for businesses and individuals, but funds with prime assets never recovered from the 2016 SEC regulation that imposed liquidity fees and gates. Institutional funds, in addition, must report fluctuating NAVs instead of a constant $1.00. As Figure 5 indicates, after a brief period of decline, total MMF assets moved above the previous year-end peak level of $3.7 trillion and reached $4.7 trillion as of May 31, 2020. Since 2016, prime funds have represented only about 20% of the overall shares at their highest point and are now at 16%. Institutional prime shares never broke above the 10% mark, compared to 36% before 2016, when they accounted for more than one third of the assets in the fund industry.

To conclude, while prime funds provide a source of funding for CP issuers and offer incremental income opportunities over government funds for investors, their systemic status has diminished meaningfully. This change in status, when combined with the more volatile nature of shareholder activity, make them a less critical part of the government’s effort to bolster system liquidity.

What Do We Do with Prime Funds?

If successive rounds of financial regulations failed to fix prime funds’ vulnerability, one cannot help but ask what else is there to fix? Requiring a higher liquidity threshold? Reducing concentration in CP and other non-government debt? While Covid-19 was to blame for a lot that went wrong in the market, we should recognize the direct link of large share redemptions in prime funds to a subsequent liquidity crunch. If the funds are to remain relevant for institutional liquidity management, the solution needs to come from the liability side of the product, possibly with external liquidity support.

Moving liquidity guidepost does not address investor confidence: Some have suggested moving the 30% weekly liquidity threshold on prime funds higher, perhaps to 50%. The downside of having a liquidity target, as was criticized before the current rule was written, is that it creates a bright yellow line for shareholders to run towards in a market liquidity event. Such a target reduces income potential in normal times and is not very effective in a run situation. As Figure 1 above demonstrates, at least half of the funds we track kept their weekly liquidity level at above 40%, but the balances dropped rather quickly in less than a week. Moving the guidepost does not remove the risk, it simply moves the yellow line.

Capping CP exposure does not address the root cause: Prime funds, by definition, are credit instruments. If the regulators want to further address credit concerns in prime funds, the attention should not focus only on CP holdings but other credit instruments as well. Who can answer the question on an appropriate level of credit exposure that will remove run risk in a market event, say 50%? Capping credit exposure through edict makes them look a bit more like government funds but does not solve liquidity concerns unless all credits are removed. We will then end up with only government funds. We think shareholders can make their own decision on the types of funds to use.

Contingent liquidity is a preferred solution: We think contingent liquidity from external sources is the most effective way to fix the structural vulnerability. This approach has been proven effective in the form of the Fed’s money market fund liquidity facility (MMLF). The facility helped reverse fund flows, calm the short-term credit markets, and negated the need for Treasury to offer guarantees. Making MMLF permanent or allowing the funds to tap into the Fed’s discount window on a contingent basis will not be an easy conversation. But it may be the most obvious solution.

Private and joint liquidity arrangements deserve a second look: Other liquidity solutions could include revisiting the “liquidity fund” proposal from the fund industry, liquidity swaps with financial institutions by individual funds. These options require high level discussions among the regulators and within the industry. Some may require the allocation of initial capital or reserves to fund liquidity pools. The current zero interest environment complicates efforts in this direction.

Shareholder Disclosure and Concentration Limits: Enhanced portfolio transparency has not been met by enhanced shareholder disclosure. Since the separation of retail from institutional shareholders, concentration risk in institutional funds increased. Better shareholder disclosure and concentration limits may force shareholders to diversify their investments and reduce flow volatility. For concentrated shareholders, distribution in kind may be invoked on redemption above a certain limit.

Reorganize prime funds as USBFs: Another approach is to reorganize the funds as ultra-short bonds funds as income vehicles and de-emphasize their liquidity promises. The funds can be organized by WAM and rating categories and be relieved of liquidity fees and gates provisions. As registered investment companies, they will continue be under the supervision of the SEC and offer daily share exchanges.

Do nothing: Doing nothing could be an option from a regulatory perspective. The recent episode may have helped investors realize the poor liquidity characteristics of prime funds and shift their primary liquidity needs to other vehicles. Further reduction of institutional prime funds as a share of the overall liquidity market may mitigate the need for regulatory actions. Recent announcements by a few fund sponsors to end prime fund offerings may be an indication of that trend.

Conflict of Interests Indicate a Long Road Ahead

Our recommendations notwithstanding, we suspect a lasting solution to prime fund reform will take time for several reasons.

Five groups of stakeholders: The quaint MMF product involves at least five groups of stakeholders: shareholders, asset managers (including bank-owned), issuers (corporate, financial, sovereign, agency and local governments), securities dealers and financial regulators (and ultimately taxpayers). Every round of regulatory reform is a balancing act to address the interests of each group.

Conflicting interests within stakeholders: Within each stakeholder group, there are additional conflicts of interest to address. The Federal Reserve, the FDIC, the SEC, and the Treasury Department are all members of the Financial Stability Oversight Council. Each represents the policy interest of the federal government from a different angle and may disagree with proposals from a different arm of the government. For example, a permanent MMLF may clear the SEC, but the Fed may not want to be permanently responsible for an industry not under its supervision, and the Treasury may worry about taxpayer losses. Similarly, shareholders often must fight for liquidity with each other in a classical Game Theory situation.

Market discipline or moral hazard: Contrary to in 2008, we have not heard the phrase “moral hazard” being used during Covid-19. For a few weeks, the Fed was the liquidity provider to most of the financial system and will remain a key plank of liquidity support for the foreseeable future. How members of the FSOC withdraw support will influence the market’s view on the liquidity characteristics of prime funds. This is not a new problem. Certain institutional shareholders pick prime funds sponsored by large financial institutions with the assumption of implicit government support. What happened in 2008 and 2020 strengthened the funds’ quasi-agency status in their minds. It is time for the government to totally extract itself from the moral hazard and encourage market discipline.

Conclusion – Liquidity or not-liquidity, that is the question.

Over the last five decades, money markets funds underwent several transformations and rounds of regulatory overhaul. The liquidity flaws exposed during the Covid-19 crisis are only the latest sign that regulators have systematically ignored or overlooked the structural vulnerabilities of prime funds.

Prime funds’ performance in episodes of market volatility is empirical evidence that the asset class is not a reliable liquidity product, at least not as a primary or contingent source of liquidity. Extraordinary measures from the federal government, while necessary to reintroduce faith in the short-term credit markets, should not be recurrent policy decisions. We think successive regulations have reduced the systemic status of prime funds in CP funding and the overall economy. While the asset class at times offers income advantage over government funds and deposit products, investors may be better served by redirecting funds to other liquidity vehicles.

We discussed why bolstering portfolio liquidity or restricting CP allocation may not resolve the inherent drawbacks of shared liquidity. Instead, a solution needs to come from external and contingent liquidity. Shareholder transparency and concentration limits may help distribute liquidity risk more evenly among the funds, and changed shareholder perception and behavior may lessen the need for regulatory solutions. Reforming the funds as ultra-short bond funds may also make sense. These and other changes may help lead to more effective form of prime money market funds. However, any permanent solution will take time, due to the conflicting interests of many different stakeholder groups.

Our research is for personal, non-commercial use only. You may not copy, distribute or modify content contained on this Website without prior written authorization from Capital Advisors Group. By viewing this Website and/or downloading its content, you agree to the Terms of Use.

Please click here for disclosure information: Our research is for personal, non-commercial use only. You may not copy, distribute or modify content contained on this Website without prior written authorization from Capital Advisors Group. By viewing this Website and/or downloading its content, you agree to the Terms of Use & Privacy Policy.