Will There Be a Renaissance for Prime Money Market Funds?

As the market’s attention was drawn to the war in Ukraine, supply chain disruptions, runaway inflation, and higher interest rates, a significant deadline quietly passed. April 11 marked the end of the comment period for the new round of money market fund (MMF) reforms proposed by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). As the Fed is poised to hike rates aggressively in coming meetings, institutional cash investors are keenly aware that their deposit rates are not likely to keep pace. Might prime MMFs be an alternative? Will the amendments alter the utility and attractiveness of prime funds to institutional cash investors? Should investors plunge in before the new rules take effect?

To answer these questions, we need to explore the pending SEC reform proposal. The short verdict is that the approval of the final rules and the associated implementation schedule may not occur until the end of the current interest rate cycle. Institutional prime funds are not likely to return to their previous status as the cash management vehicles of choice due to a reduced amount of yield advantage over government funds. An existential threat comes from the “swing pricing” mechanism which, if approved, may result in some funds being shuttered or converted to government funds, creating challenges for shareholders who decide to remain in prime.

Background and Timing of Proposed Amendments

In March 2020, the start of the COVID-19 pandemic plunged financial markets into a fresh liquidity squeeze as investors stepped away from credit instruments and fled into the ‘safe haven’ of Treasury securities. Several institutional prime MMFs saw large redemption orders that pushed their weekly liquid assets near or through the 30% threshold that would require them to consider liquidity fees and redemption gates for redeeming shares. The Federal Reserve quickly brought back a suite of crisis-era liquidity measures and the rapid response eventually stemmed the tide and returned the market to some semblance of normalcy. But market participants agreed that measures introduced by the SEC in the last two rounds of MMF reform in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis were either insufficient in protecting funds from liquidity risk, or, in the case of “fees and gates,” perpetuated the runs. It was a foregone conclusion that a new round of rule changes was needed to finish the task.

In a 3-2 vote on December 15, 2021, the SEC voted to propose amendments to Rule 2a-7 that governs money market funds. In addition to tackling the fees and gates issue, the proposed amendments tightened up liquidity requirements, introduced a swing pricing mechanism to equalize liquidity costs for all shareholders, and imposed reporting requirements on shareholder information. The public was invited to comment on the amendments through April 11, 2022, after which the agency would review the comments and publish final rules.

When will the amendments come into full force? The SEC proposed a twelve-month compliance period for swing pricing and six months for minimum liquidity requirements, with the removal of liquidity fees and gates going into effect immediately. However, assuming the agency will need six months to digest the comments and publish the final amendments, it is highly unlikely that MMFs will be required to be fully compliant before the end of 2023. Vacancies at the SEC introduce more uncertainty, since neither of President Biden’s nominees to the Commission, Jaime Lizarraga and Mark Uyeda, participated in voting on the proposals. They may need time to form their decisions before a final vote can take place. The timing of the pair’s confirmations in a 50-50 Senate is another unknow factor. Given all these factors, the chance of the amendments taking full effect before 2024 appears to be quite low, by which time the current rising rate cycle may have run its full course.

What Does the Proposal Contain?

Improved liquidity requirements: The requirements for daily and weekly assets will be increased from 10% and 30% to 25% and 50%, respectively. Based on shareholder behavior in March 2020, the SEC believes the increased thresholds would provide a more substantial buffer against disorderly shareholder redemption.

Removal of liquidity fee and redemption gate provisions: Market participants have often criticized the provisions to consider a liquidity fee of up to 2% and/or temporary suspension of redemptions (gates) when weekly liquid assets drop below 30%, because they turned out to have an opposite effect on shareholder behavior than was originally intended. The proposal would remove the fees and gates provisions from Rule 2a-7 effective immediately.

Swing pricing: A swing pricing mechanism will be added to institutional prime and tax-exempt funds when daily redemption requests are above 4% of fund assets and the measure is designed to ensure that all shareholders share the costs of forced selling and discourage the first mover advantage in a liquidity event. The “swing factor” is the estimated cost of trading and other related expenses in selling a pro rata portion of every security in the portfolio. It is then subtracted from the net asset value (NAV) for outgoing share transactions. Industry participants fiercely opposed the controversial mechanism, arguing it was impractical to estimate a swing factor from unobservable trading dynamics in a same-day liquidity vehicle, especially in a turbulent market with reduced liquidity. Following this pushback, the SEC has requested additional feedback on this amendment, leaving the door open for tweaks or walk-backs.

Other notable amendments: The proposal requires that fixed-NAV funds, namely government funds and retail prime funds, convert to floating NAVs when market conditions cause the fund yield to become negative. This essentially puts a stop to the practice of negative share distribution employed by offshore euro-denominated funds in recent years. Reporting requirements on forms N-MFP, N-CR and N-1A are updated to reflect the rule changes and to improve transparency on portfolio holdings. For the first time, institutional prime and tax-exempt funds will be asked to report shareholder composition and concentration at the beneficial ownership level. Capital Advisors Group advocated for this requirement as early as 2010, believing it is critical to understand the liquidity impact from large shareholders in a shared liquidity vehicle. Other new disclosure requirements include security identifiers, trade date and yield at purchase, as well detailed information on repurchase agreements (repos) such as counterparties, clearing status, and collateral delivery, etc.

Implications for Prime MMF Utility

In the decades leading up to the 2016 reforms that introduced floating-NAVs, fees, and gates, institutional prime funds were preferred cash management vehicles for liquidity investors due to their ease of use and attractive yield pickups over bank deposits. The subsequent migration from prime to government funds resulted in a much smaller footprint for institutional prime while overall MMF assets climbed to new peaks. Will this round of rule revisions reinstate investor confidence in prime funds’ cash-like functionality? Will institutional prime funds have a renaissance that rivals their golden age at the turn of the millennium? Unfortunately, we think that if the amendments are ratified as proposed, institutional prime funds will be less distinguishable from government funds and be more cumbersome to manage than ultra-short bond funds, thus making it unlikely that they once again become a popular cash management vehicle. However, if the industry can solve the swing factor puzzle, prime funds may offer some benefit to investors who desire credit exposure in a very low-duration shared-liquidity vehicle.

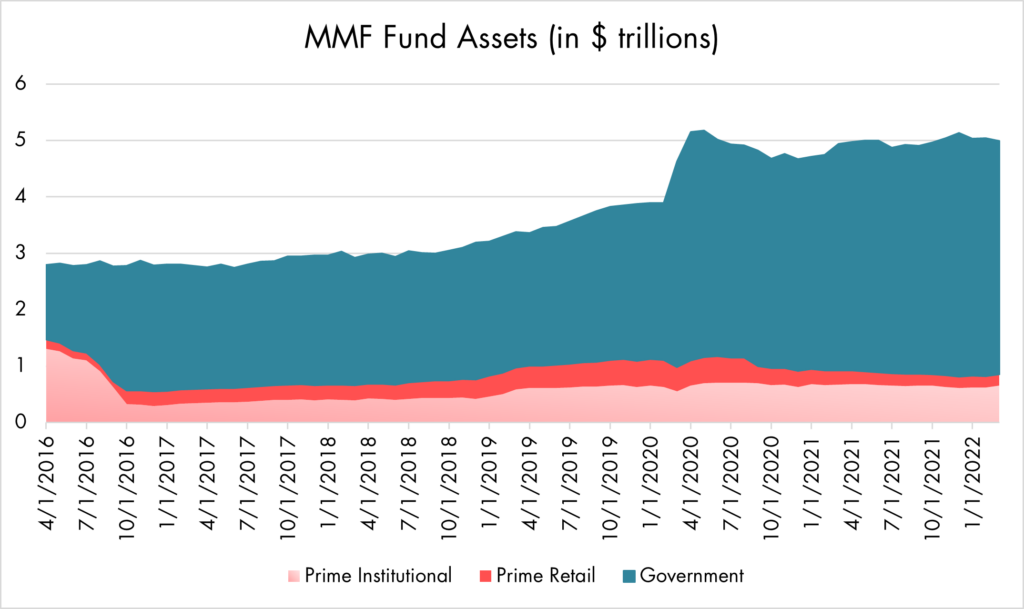

Figure 1: Institutional Prime vs. Overall MMF Assets

Source: Office of Financial Research, U.S. Department of Treasury

The Good News: The removal of fees and gates, the universally loathed provisions of the 2016 amendment, is clearly the brightest spot in the proposal. The benefit offered by fees and gates was always dubious. Few fund managers would contemplate invoking them, but shareholders preferred to steer clear of them out of an abundance of caution. At the risk of stating the obvious, prime funds regulated by Rule 2a-7 offer better protection than ultra-short bond funds with respect to credit quality and liquidity standards. A similar safety argument can be made when considering private liquidity funds, since private funds are managed according to prospectuses, not by regulatory mandate, and are subject to board discretion. Higher daily and weekly liquid asset levels improve portfolio liquidity, at least on paper, as funds tend to keep liquidity levels well above regulatory minimums. Disclosures on shareholder composition and concentration, as well as enhanced security level transparency data, alert investors to large shareholder concentration and help them better understand portfolio holdings.

The Bad News: Higher liquidity requirements often mean lower yield potential. Keeping daily and weekly liquid assets to least 25% and 50%, respectively, limits what a fund can buy to very short-term instruments, such as daily repos or commercial paper well inside of 30 days. A fund may be less able to take advantage of the term structure of interest rates, commonly known as the yield curve, that normally compensates longer-term securities with higher yield. The same amendment will be applied to all funds, not just institutional prime funds, thereby diminishing the competitive advantage of government funds over bank deposits as well. This is an unfair punishment for government funds, since they did not experience large withdrawals in March 2020 but were rather the recipients of inflows. In a related issue, prime funds’ potential yield pickup over government funds will also be reduced thanks to smaller credit spreads over risk-free Treasuries when maturities are shorter. Shareholders may be less inclined to switch from government back to prime if the potential reward does not justify the risk.

The Ugly News? Many commentators, both before and after the proposal hit the wire, voiced concerns that swing pricing on MMFs is unworkable without significant systems retooling. In essence, the SEC swapped one bitter pill, the liquidity fee, for this more exotic remedy. The measure is essentially a dynamic liquidity fee: when redemption is less than 4% of net assets, the swing factor is an estimate of the transaction costs from brokerage, custody and other actions associated with selling a theoretical “vertical slice” of all the securities in the portfolio, not just the most liquid assets. This factor is subtracted from the NAV for redemptions. When requests exceed 4% of net assets, an additional “market impact factor” is added as a good faith estimate of selling the same securities under current market conditions. While this provision is common to Europe-based mutual funds, introducing it to the US will be challenging due to early trading cutoffs in a country with multiple time zones. The vast network of third-party intermediaries will need to provide real-time shareholder transaction requests to the fund manager to calculate the swing factor. Funds that strike multiple NAVs throughout the day will be hard pressed to estimate multiple intraday swing factors. These operational challenges are in addition to the reality that many money market securities are not expected to be actively traded, especially during a rapidly deteriorating market liquidity event. Thus, this provision could very well be the signal for some institutional prime fund operators to throw in the towel, saving expensive human and financial capital on a product with significantly reduced shareholder appetite and little yield differentiation from government funds.

Will There Be a Renaissance for Institutional Prime Funds?

If swing factor provisions survive the final rule, it is difficult to fathom how institutional prime funds will be able to thrive.

As proposed, the amendments do not make enough economic sense for institutional prime funds to remain attractive to shareholders and funds sponsors alike. As noted earlier, the explicit concentration, liquidity and disclosure requirements offer robust shareholder protection when compared to similarly managed private liquidity and ultra-short bond funds. However, higher liquidity requirements put prime funds at a yield disadvantage compared to the two alternatives. In addition, liquidity investors are notoriously risk averse, especially to cash vehicles with esoteric features. Swing pricing will be a tough sell to this crowd.

The fund industry and its intermediary partners are faced with a different set of challenges. After undergoing a long and arduous process of converting their systems to handle floating-NAVs and fees and gates, they have fresh decisions to make. Will they commit significant financial and human capital to design and implement a new system to accommodate more rule changes on a product with less cash-like utility while alternatives are available? We suspect that swing pricing may become the straw that breaks the camel’s back to force some, if not all, fund sponsors to end prime fund offerings. Funds that decide to stay in the game must then contend with their smaller footprint in the short-term credit markets with less pricing power over commercial paper and Yankee CD issuers.

How Regulatory Changes Will Impact Liquidity Investors

The March 2020 liquidity event put an abrupt stop to the slow but steady flow back into prime MMFs. Institutional prime funds tracked by Crane Data lost $110 billion in assets, falling from $615 billion in February 2020 to $504 billion in March 2020. By April 2022, the figure had climbed back up to $637 billion, compared to $2.85 trillion in combined institutional Treasury and government funds.

Prime to government migration: We think that many of the current institutional prime assets will be converted to government funds at or before the effective date of the final rules. Since we are probably at least 18 months away from that deadline, prime assets can conceivably grow further before the migration starts. We don’t advocate adding to prime fund exposures due to their current shortcomings of floating NAVs and fees and gates, but we can envision some adventurous investors willing to risk NAV volatility for higher yield over government funds in the interim period.

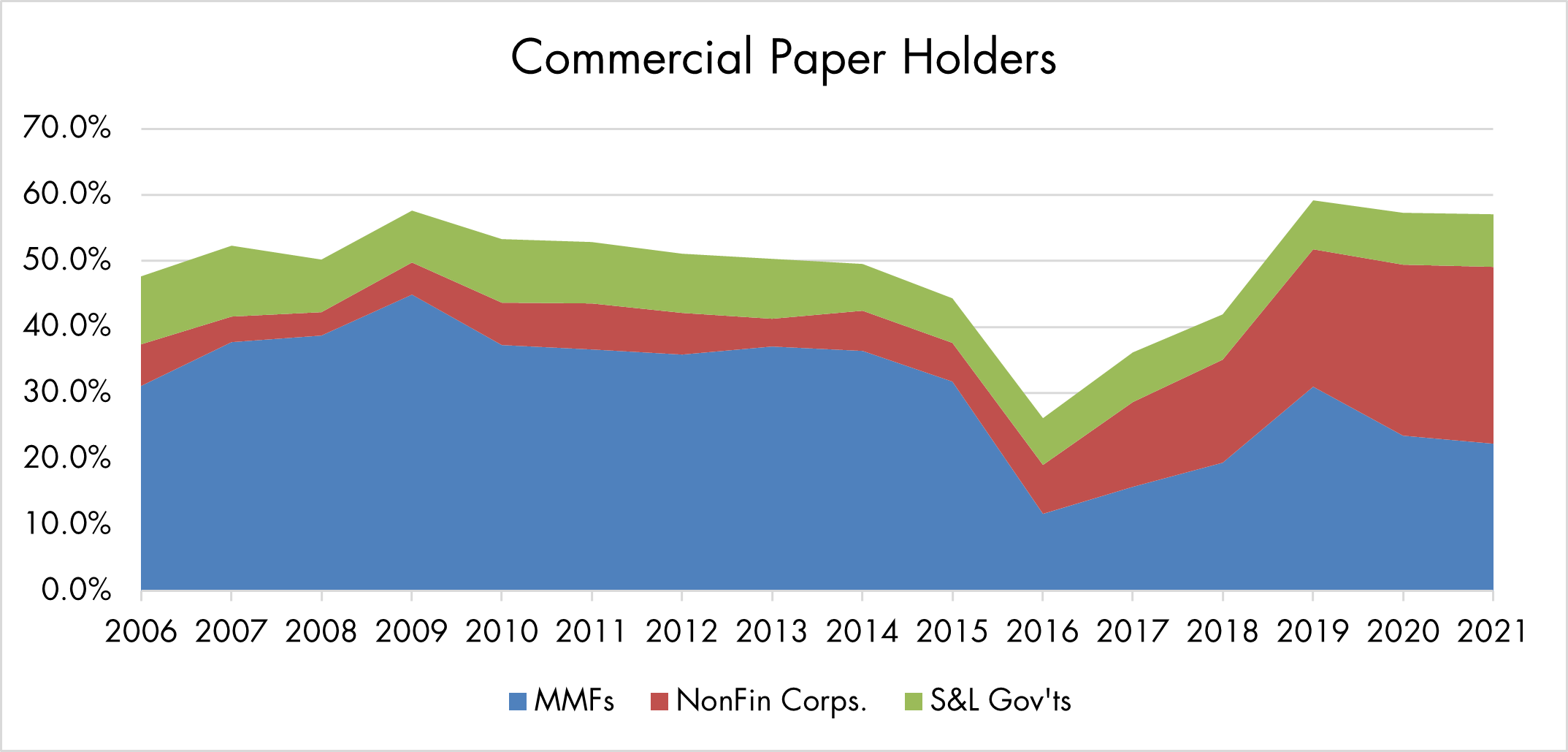

Incrementally wider spreads and lower liquidity: As prime assets decrease, reduced investor demand for credit instruments such as commercial paper and Yankee CDs will cause spreads to widen. Many large issuers in the short-term credit space maintain diverse funding channels, so this should not pose a meaningful threat to the overall market. As a point of reference, prime funds’ share of the CP market declined from 45% in 2009 to 22% in 2021, according to the Federal Reserve’s z.1 reports. Issuers more dependent on prime MMFs for funding will need to adapt and adjust to the new environment. As issuers find other investor groups to fill in the gap, market liquidity may be incrementally poorer as new buyers are likely to be smaller and more diverse, which incidentally could be more desirable for issuers.

Figure 2: Major Holders of Commercial Paper

Source: Federal Reserve Z.1 Financial Accounts of the United States

Lower yield potential on all MMFs: As we have noted, higher overnight (25%) and weekly liquid assets (50%) requirements are applicable to all MMFs, not just institutional prime. For prime funds, this means the yield will be pinned to overnight and 7-day credit instruments, which offer lower pickups to daily repo rates. Government securities with maturities less than 60 days and all Treasury securities qualify as weekly liquid assets, so higher daily and weekly requirements will also put government funds at a disadvantage over direct investments and separately managed accounts (SMAs) that can invest out on the yield curve. This issue will become more pronounced when the Fed reverse repo program (RRP) rate underperforms other liquid instruments in a steeper yield curve environment.

Playing the waiting game: Many factors will influence how this latest round of MMF reforms will impact liquidity investors. A divided Senate in a mid-term election year makes the fate of the two SEC Commissioner nominees uncertain. If they are confirmed, it is uncertain if either or both will support a final vote on all the amendments in the proposal. Overwhelming objection to swing pricing based on operational difficulty may persuade the SEC to find a different approach. The Commission may try to smooth out the transition by allowing a longer implementation window. All these factors lessen the chance of the new rules being approved and finalized within the next 18 months. While the waiting game is on, prime funds may gain some assets in the interim from opportunistic investors who may plan to move out of prime at the last minute. We continue to advocate for government funds for overnight and near-term cash needs while investing out on the yield curve in high quality government and corporate securities that offer better risk-adjusted return profiles.

Please click here for disclosure information: Our research is for personal, non-commercial use only. You may not copy, distribute or modify content contained on this Website without prior written authorization from Capital Advisors Group. By viewing this Website and/or downloading its content, you agree to the Terms of Use & Privacy Policy.