Investing in the European Bank Debt Markets

What happened with Credit Suisse and what cash investors may be able to take away from the experience.

Amidst the recent turmoil in the banking system, investors have taken a renewed interest in their bank debt holdings, particularly in the case of Credit Suisse. In a highly unusual move, regulators flipped the established creditor hierarchy by placing the bank’s Additional Tier-1 notes (AT1s) below its common equity. The move raised questions about AT1s and the risks to the broader bank creditor class.

This blog delves into the Who, the What, and the possible Why of European bank AT1s, and what cash investors may be able to take away from the Credit Suisse experience. We believe that this experience illustrates why European bank AT1s, and other subordinated notes, are incompatible with cash investment mandates. We further recommend that cash investors interested in European bank debt may want to stick solely to senior bank paper. These bonds carry the highest protection from losses both via structural subordination and probability of government support. Moreover, the opportunity cost to cash investors of omitting other forms of European bank debt issuance is not significant.

What are Additional Tier-1 notes (AT1s)?

AT1 notes are a form of subordinated debt that banks issue to meet regulatory MREL (Minimum Requirement for own Funds and Eligible Liabilities) and TLAC (Total Loss-Absorbing Capacity) requirements. These two requirements were both designed post-financial crisis and with the same end goal in mind, to shift the assumption of losses from governments and taxpayers (via “bail-outs”) to a bank’s own creditors. This process is referred to as “bail-in”; e.g. debtholders, rather than the government, act to recapitalize a bank by accepting write-downs or conversion to equity.

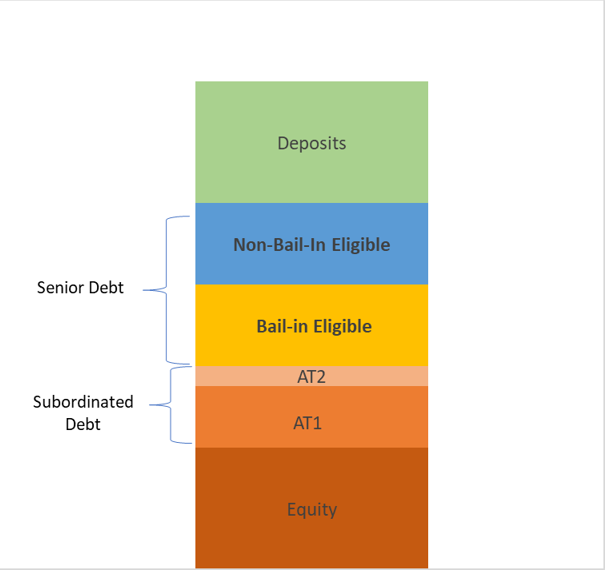

AT1 bonds are perhaps the most important aspect of this new regime. As Figure 1 illustrates, AT1s rank ahead of only equity holders in seniority of claims. They are issued as perpetual securities, with initial call dates any time between 5-10 years. They have built in contractual obligations that mandate an explicit assumption of losses if a bank reaches the “Point of Non-Viability” (e.g. when it is deemed to be failing or likely to fail). This typically takes the form of a permanent write-down or conversion to equity.

AT1 coupon payments are discretionary and non-cumulative, meaning that if a bank misses a payment, it is not required to make it up. Restrictions on AT1 coupons can also be placed on a bank if its capital levels fall below certain regulatory thresholds. The risks of non-payment and potential losses means that these securities carry low ratings (typically in the BB range) and demand a high-yield premium from investors.

Figure 1: Bank Capital Stack

What Happened in The Credit Suisse Case?

As part of UBS’ agreed acquisition of Credit Suisse, Credit Suisse’s equity holders received $3.3 billion in UBS shares. However, the bank’s AT1 notes were written off completely by the Swiss regulator FINMA as a way to make the deal more palatable for UBS’ management. The move effectively placed AT1 notes subordinate to equity, in disregard to the established creditor hierarchy.

The move was highly controversial, with other regulators such as the European Central Bank and Bank of England quickly distancing themselves from the Swiss authorities. Both issued statements attempting to calm markets, affirming that AT1 holders would not be treated this way in their jurisdictions. The EU’s Bank Resolution Directive (BRRD) would seem to support this view, as it explicitly mandates that capital instruments must be written down in “accordance with the priority of claims under normal insolvency proceedings”.

What Did We Learn About AT1s?

Nevertheless, this episode illustrates the risks associated with subordinated instruments of this nature. In all cases where a European bank enters resolution, or is provided with government support, investors in AT1s should assume that they will take a haircut (if not a full write-down). That is in fact the whole point of these debt instruments existing in the first place. As such, they are not appropriate for investors whose primary objective is preservation of principle1.

What are The Alternatives to AT1s?

More relevant for cash investors are the senior debt tranches. European banks broadly issue two types of debt at the senior level: bail-in and non-bail-in eligible. Non-bail-in bonds are the traditional form of senior obligation. They are the highest priority unsecured debt obligation in a bank’s capital stack. Typical issuance takes the form of long-term notes (generally 2-10 years) or commercial paper. They are structured as bullet maturities, though some notes may be issued with a call feature that allows for early redemption.

Bail-in bonds are a newer, post-financial crisis issuance type. They are structurally subordinate to non-bail-in-eligible notes, making them effectively a “junior” senior obligation. To be eligible for the “bail-in” tag, and inclusion in TLAC/MREL ratios, the debt issuances must be unsecured and have a remaining maturity of at least 12-months. However, in contrast to AT1 notes, senior bail-in notes are not subject to explicit loss triggers, meaning that imposition of losses on this debt class is up to the discretion of the regulatory body.

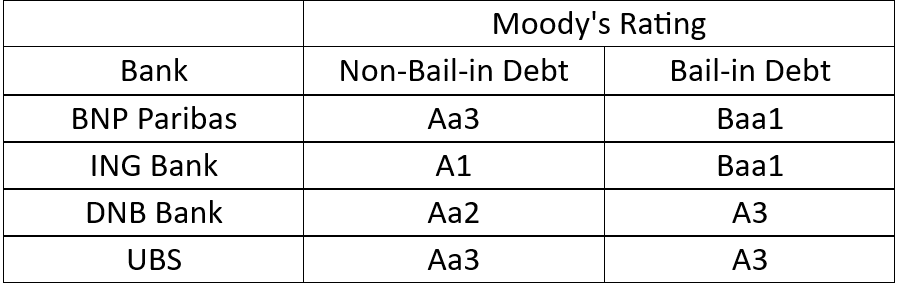

Under ratings agency frameworks, non-bail-in debt is typically rated 3-4 notches higher than bail-in debt. This is due to the higher seniority as well as an assumption that governments are more likely to provide support to non-bail-in debtholders. This makes ratings a useful tool in identifying the type of debt bondholders own.

Figure 2: Sample Ratings – Bail-In vs. Non-Bail-In Debt

Where Should Cash Investors Be?

Given their investment policy and risk requirements, we’d advise that the majority of cash investors default to senior unsecured non-bail-in issuances and consider bail-in debt on a case-by-case basis. Much depends on ratings level and availability of supply, as certain issuers may have bail-in debt that is compatible with policy requirements and others may not.

Using Bloomberg, we estimate bail-in debt comprises 43% of the investible European corporate debt market for cash investors2. Of this universe, the median option-adjusted-spread (OAS) on the bail-in notes was 164 basis points, while the median OAS of the non-bail-in group was 122 basis points3. This conforms to results from a BIS paper4, which also found that the spread is positively correlated with market conditions (meaning it widens when credit conditions worsen, and vice versa). Since higher spreads tend to occur during periods of higher market risk, and typical cash investors often want to own better-quality names during those periods, the risk of owning bail-in debt over non-bail-in debt may outweigh potential yield pickups. Thus, to the extent several classes of debt exist from the same issuer, investors should give preferences to senior non-bail-in debt before bail-in debt and avoid AT1 debt altogether.

1The same may be true with AT2s and any other form of subordinated debt issuance.

2Derived using Bloomberg fixed income search function. Parameters are dollar-denominated investment-grade corporate bonds issued by European-based banks (excluding UK), with a maturity of 3-years or less, and a payment rank of Senior Unsecured, Senior Preferred, or Senior Non-Preferred. Amongst this group we rely on Bloomberg’s bail-in designation to denote bail-in vs. non-bail-in eligible notes. Data as of 5/2/23.

3Relies on Bloomberg BVAL pricing

4BIS Working Paper #831: “Believing in bail-in? Market discipline and the pricing of bail-in bonds”, by Ulf Lewrick, José Maria Serena and Grant Turner. https://www.bis.org/publ/work831.pdf

Please click here for disclosure information: Our research is for personal, non-commercial use only. You may not copy, distribute or modify content contained on this Website without prior written authorization from Capital Advisors Group. By viewing this Website and/or downloading its content, you agree to the Terms of Use & Privacy Policy.