What Dwindling Excess Savings Means for The Consumer

When will “revenge spending” exhaust consumers’ pandemic-era savings? What does this mean for consumption and growth?

Introduction

Excess savings have become a marque piece of economic outlooks, attempting to estimate when consumers’ “revenge spending” will exhaust bank accounts leading to a drop in consumption. However, Q3 2023’s 4.9% annualized GDP growth, most of which was driven by private consumption, has proven that reports of the U.S. consumers’ ‘death’ have thus far been greatly exaggerated. This concern is not unwarranted, however. Personal income growth has remained below headline PCE since May 2023, eating into consumers’ spending power. Additionally, COVID-19 pandemic-era support programs including the student loan moratorium have ended and a rapid increase in 10-year Treasury yields since April has greatly increased financing costs across the economy. There is little debate about the direction (down) and level (low) of excess savings remaining, but even when excess savings are removed from the picture, the U.S. consumer remains in very strong standing. Barring a material rise in unemployment, consumers should continue to keep the economy and consumer sensitive credits, such as banks, cyclicals, and asset-backed securities, moving along.

“Revenge Spending”

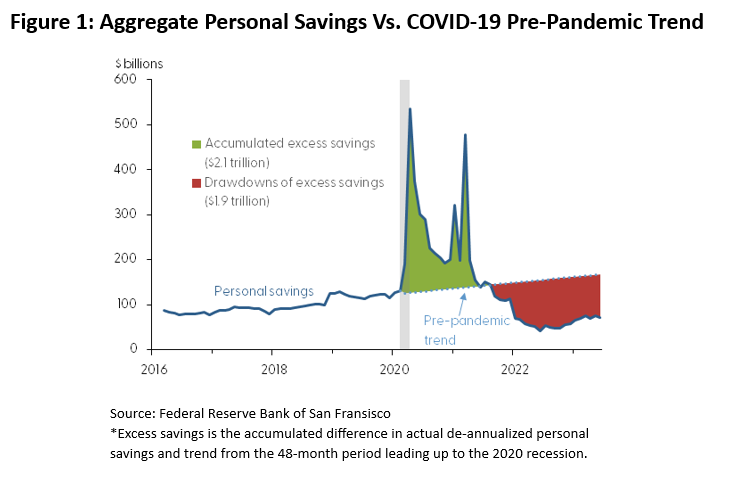

Pandemic-era stimulus programs combined with few opportunities to spend created a boon for consumer bank accounts, pushing households to save significantly more than they would have otherwise. The Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco estimates aggregate excess personal savings peaked at $2.1 trillion in August 2021. Consumers have since used this to drive private consumption, which accounts for ~ approximately 2/3 of GDP. The San Francisco Fed estimated there was approximately ~ $190 billion of excess savings remaining as of June which they estimate should have been depleted sometime in the third quarter.

While these figures are helpful to understand the broader picture, estimates of excess savings and when they may run out vary widely based on trend assumptions and projected economic conditions. Additionally, while excess savings certainly supported spending since the pandemic, they alone do not explain the extremely strong post-pandemic consumption numbers.

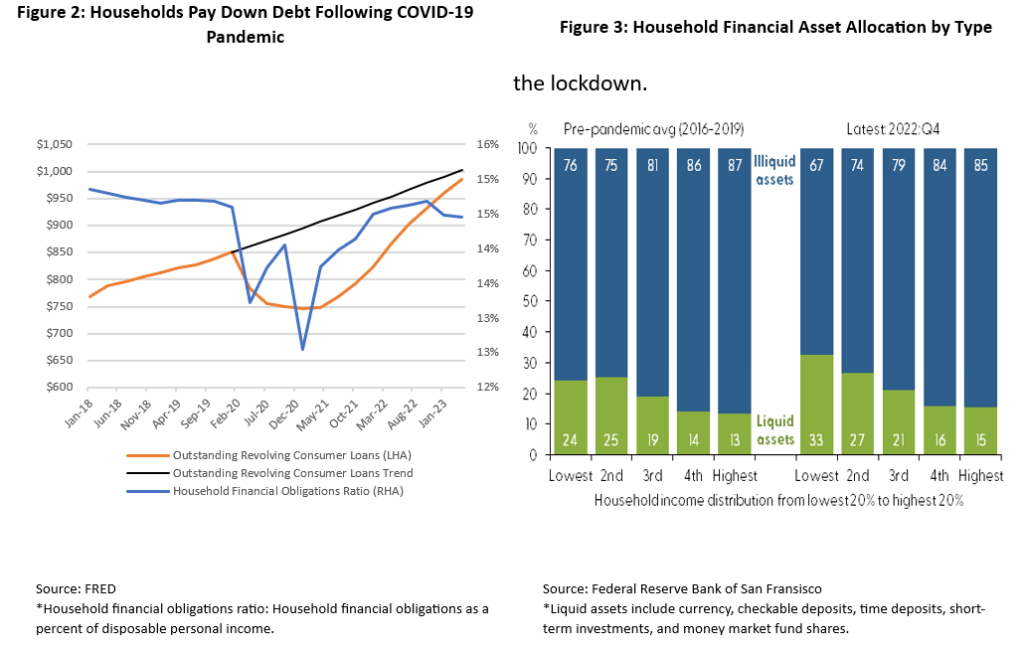

The financial flexibility awarded by pandemic conditions gave households the opportunity to bolster balance sheets, largely by increasing liquidity and paying down debt. Household liquidity profiles were obviously helped through government transfers and loan deferral programs, but the return of rock bottom rates also allowed many homeowners to refinance their homes and obtain more affordable monthly payments. Additionally, a sharp rise in home prices allowed owners to unlock liquidity through home equity lines of credit. This excess liquidity helped consumers to reduce auto, credit card and other types of debt, significantly reducing their financial burden. Following this repositioning, consumers had both the liquidity to increase purchases and the financial headroom to borrow, providing an afterburner for private consumption, without overextending themselves financially. This allowed consumers to take advantage of spending opportunities, largely on experiences, leading to “revenge spending” following the lockdown.

Where’s the Stress?

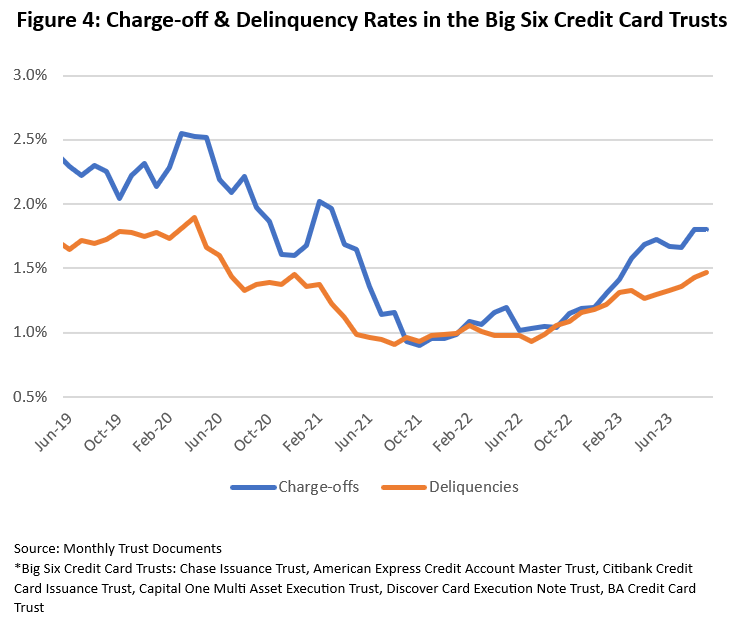

Common sense and sensible economics suggest that high inflation, high interest rates, and revenge spending should have pushed consumer finances, and with-it economic growth, backwards. So far, we haven’t seen the rapid deterioration in consumer asset quality one may expect, but we are beginning to see the wind in consumers’ sails slow. Charge-off and delinquency rates in the Big Six credit card trusts have begun to rise but remain well below pre-pandemic levels.

Admittedly, the Big Six credit card trusts tend to produce better asset quality metrics than some of their peers. However, Moody’s tracks quarterly loan performance metrics at the largest US retail banks and notes that auto and credit card loan charge-offs in this cohort were 31bps above and 9bps below 3Q 2019 levels, respectively. Moody’s anticipates auto loan defaults will peak in 2024 at 1.5% compared to 1.0% in 2019, and credit card defaults will peak at 4.5% compared to 3.5% in 2019. These projections assume the unemployment rate peaks at 5%, significantly higher than the exceptionally strong 4.0% 2019 peak unemployment rate, which fell to 3.5% by September.

The resumption of post-pandemic society has given consumers the opportunity to normalize their finances from extremely strong levels by spending and borrowing without overextending themselves. Part of this can be seen in Figure 2, displaying the household financial obligations ratio which has returned to 2019 levels of approximately ~14% and remains well below the 18% peak recorded directly before the global financial crisis.

Slowing Tailwinds

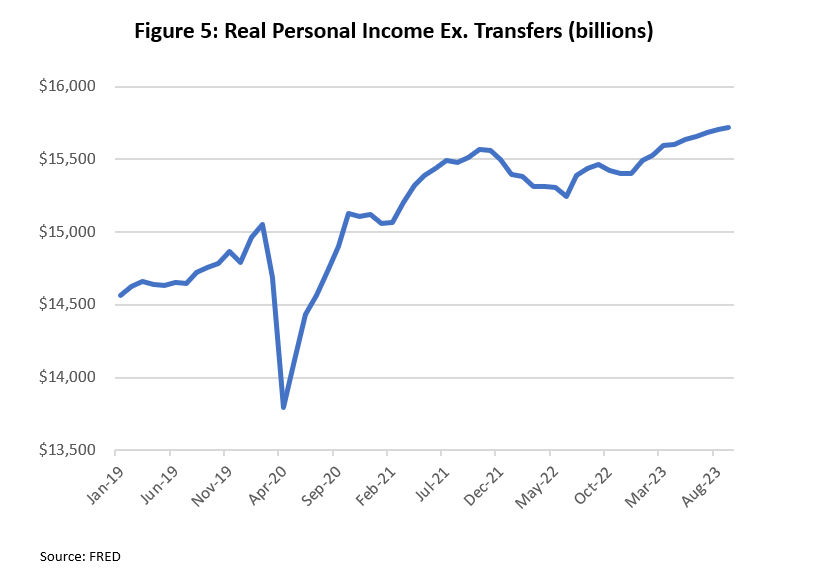

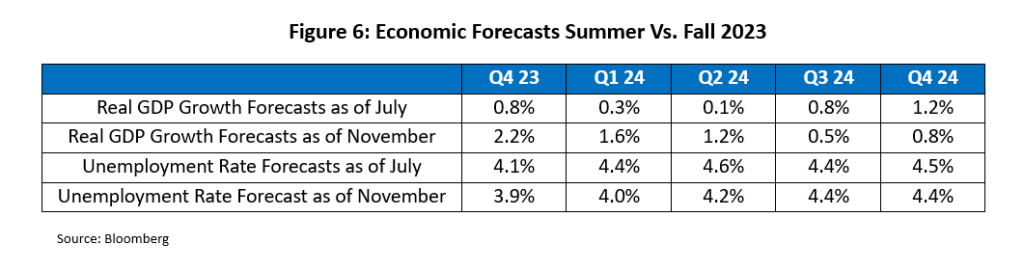

Depleted excess savings, lower levels of liquidity, and outstanding consumer credit returning to trend should slow the wind in consumers’ sails but shouldn’t stop the ship. Ultimately, the real be-all and end-all when it comes to consumer finance is employment opportunities. Taking a broader view, households seem to remain on solid footing. Employment opportunities remain robust, debt isn’t excessive, and inflation has continued its downward march towards a more comfortable 2%. While the unemployment rate has moved 50bps higher in recent months to 3.9%, it remains 10bps below what the Fed considers consistent with 2% inflation suggesting the labor market continues to be overheated. Additionally, wage growth has been robust leading to higher levels of real personal income than before the pandemic. While high inflation in 2022 did significantly reduce purchasing power, if prices stabilize moving forward as expected the trend of real wage growth will likely continue. While signals do point to a cooling labor market, expectations for an unemployment rate in the 4%-5% range through next year is remarkably strong from a historical perspective. These strengths have led forecasters to upwardly revise growth and employment forecasts for the end of 2023 and first half of 2024.

The tailwinds which have driven the post-pandemic spending spree will inevitably subside, but the outlook is not completely bleak without them. Once gone, the economy will more likely experience a slowdown in growth from high levels rather than an outright contraction. However, significant risks to household finances remain. Higher-for-longer rates will likely reduce consumers’ ability to finance homes, autos, and durable goods. Geopolitical conflicts could lead to resurging inflation reducing consumers’ spending power just as inflation looks to be subsiding. Tighter financial conditions could spark turmoil which could spread into the real economy. Unfortunately, if one or all these occur, unemployment almost always takes the elevator up and stairs down, which could greatly impact household balance sheets. However, for the time being consumer finances remain strong, but pandemic fortunes are running low, which will likely slow but not stop growth. For cash investors, this means that consumer focused credits such as banks, cyclicals, and consumer asset-backed securities remain supported, but require somewhat of a watchful eye.

Please click here for disclosure information: Our research is for personal, non-commercial use only. You may not copy, distribute or modify content contained on this Website without prior written authorization from Capital Advisors Group. By viewing this Website and/or downloading its content, you agree to the Terms of Use & Privacy Policy.