Where is the Neutral Rate?

Could potential changes in the economy from the end of the Fed’s tightening cycle lead to a higher neutral rate?

Introduction

With the Federal Reserve System (the “Fed”) nearing the end of its tightening cycle, the question for investors has shifted to whether rates can truly remain “higher for longer”, to quote the current in-phrase of economists and forecasters everywhere. Put more simply, does the rise in interest rates have legs, or is it a temporary phenomenon?

At the heart of this question is the level of the so-called “neutral” Fed funds rate. The neutral rate – first described by 19th century economist Knut Wicksell – generally refers to the rate consistent with an economy that’s operating at full capacity. In the modern context, this is viewed as something like full employment, 2% inflation, and GDP growth in line with potential.

The neutral rate can be broken down into two components: the real rate (often referred to as r*) and the inflation premium. We are not prognosticators, but we are seeing changes in the economy that could drive both these components upwards, translating to a potentially higher neutral rate.

R*

1.Durability of Economic Recovery

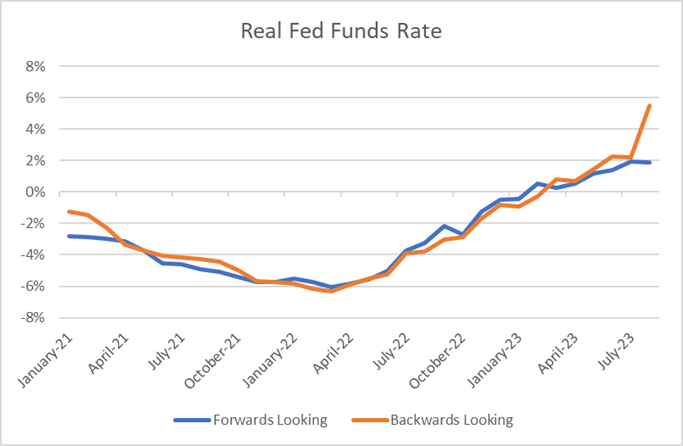

One reason to believe that the neutral rate is rising is simply that the economy continues to perform well despite a significant tightening of monetary policy. While there is no universal way to measure the stance of monetary policy, a useful proxy is the real Fed funds rate, which is simply the Fed funds rate minus inflation. The stark rise in the real Fed funds rate exemplifies just how significantly policy has tightened over the past 18 months.

Figure 1: Bloomberg, BEA, NY Fed. Forward Looking Rate = Fed Funds Rate – 12M Inflation Expectations (NY Fed Survey). Backwards Looking Rate = Fed Funds Rate – 12M PCE Inflation

The pass-through from this policy tightening led to a myriad of recession forecasts from economists in the first half of 2023. However, economic activity has held up well so far this year, with real GDP growth running above 2%, unemployment below 4%, and wage growth now outpacing inflation. This in-and-of-itself may be de-facto evidence of the economy’s ability to support a higher r*, as noted by Richmond Fed President Barkin.

2. Higher Public Debt

The fiscal outlook has deteriorated this calendar year, with the fiscal deficit for 2023 now projected to be well above $1.5 trillion and debt-to-GDP expected to resume its upwards trajectory after a modest decline from 2020-2022. The CBO now projects that if tax and spending policies remain on their current trajectory, federal debt could balloon from 98% to 181% of GDP over the next three decades. Such a level is not necessarily unsustainable – Japan has a 216% debt-to-GDP ratio – but the increased amount of financing needed to support the debt could put upward pressure on r*.

3. AI & Productivity Growth

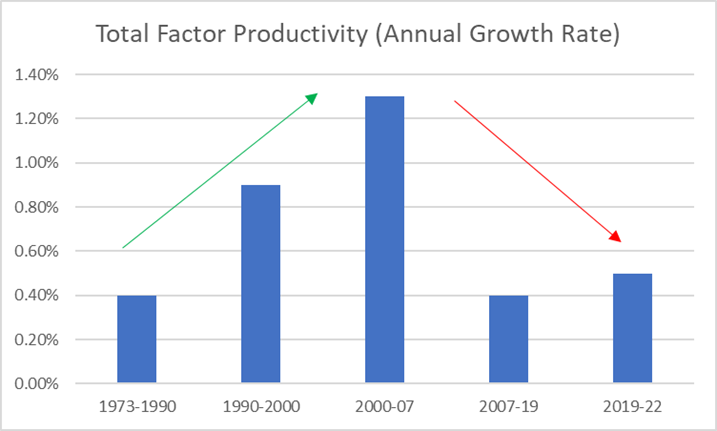

In a developed economy such as the U.S., productivity and labor force growth are the two primary factors impacting potential output, and thereby r*. On the labor side, the birth rate is falling, and immigration policy remains restrictive, suggesting that a surge in the growth rate of the labor force is unlikely.

That leaves productivity growth, which has been lackluster since the onset of the digital revolution in the mid 2000s.

Figure 2: Bureau of Labor Statistics

The rise of generative AI technology such as ChatGPT has renewed optimism about the outlook for productivity growth. A report released by McKinsey estimated that there could be upwards of $4 trillion in economic value from use of generative AI in customer service, marketing and sales, software engineering, and research & development (amongst other things). Similarly, Goldman Sachs estimates that the technology could increase global productivity growth by 1.5 percentage points over a ten year period, raising global output by 7%.

This is entirely speculative, of course. However, the tangibility of use cases for generative AI relative to other Silicon Valley fads – namely social media apps and cryptocurrency – is reason alone for optimism.

Inflation Premium

1.De-Globalization Trends (Friend-Shoring) and Supply-Side Stressors

For years, globalization was cited as a reason for structurally low inflation. The logic is relatively intuitive; in opening their borders to the free flow of capital, countries allowed firms to coordinate their supply chains to produce goods/services at the lowest possible cost. This, in turn, was passed on to consumers in the form of lower prices.

Secondarily, the free flow of capital resulted in a proliferation of dollar assets across the globe, particularly to countries with high levels of savings such as China. Former Fed Chair Ben Bernanke often referenced this phenomenon as the “Global Savings Glut” and cited it as a reason that U.S. interest rates were low compared to peers.

These days this is in the process of reversing itself. Geopolitical tensions between the East and West have risen significantly, resulting in imposition of tariffs, economic sanctions, and restrictions on foreign investment. Moreover, after seeing how frail their global logistics networks proved to be during the pandemic, companies are increasingly opting to “friend-shore” or “nearshore” their supply chains. The upshot is likely to be higher prices and reduced foreign demand for dollar assets on the margin, both of which would act to put upward pressure on the neutral rate.

2. Demographics

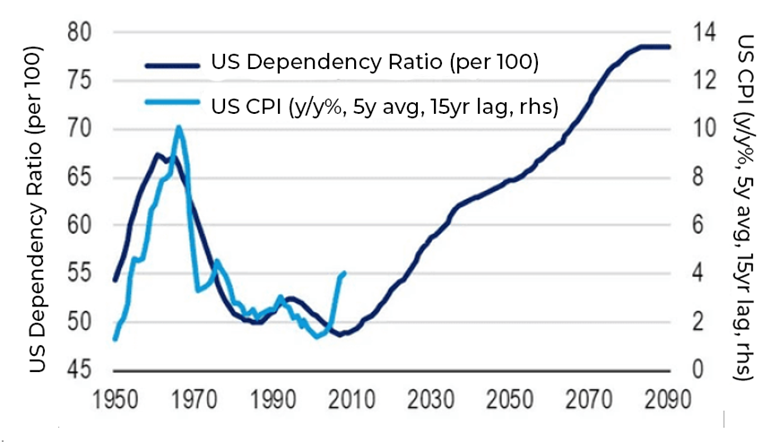

It should come as a surprise to no one that the U.S. population is increasingly aging into retirement. Barclays estimates that the so-called dependency rate (% of the population not in the labor force) will rise by 4 percentage points over the next decade or so due to population aging. There’s some evidence that this correlates positively with inflation (as shown in figure 3), as those outside of the labor force (e.g., kids and retirees) tend to spend more and save less than people who are working.

Figure 3: Daily Shot, BOA Global Research

Assuming the projected rise in the dependency ratio manifests, we would expect this historical correlation to continue. This, in turn, would put upwards pressure on the neutral rate (all other factors equal). Barclays estimates that the positive impulse to the neutral rate could be as great as 0.4-0.5 percentage points.

3. Fed Tolerates Higher-Inflation

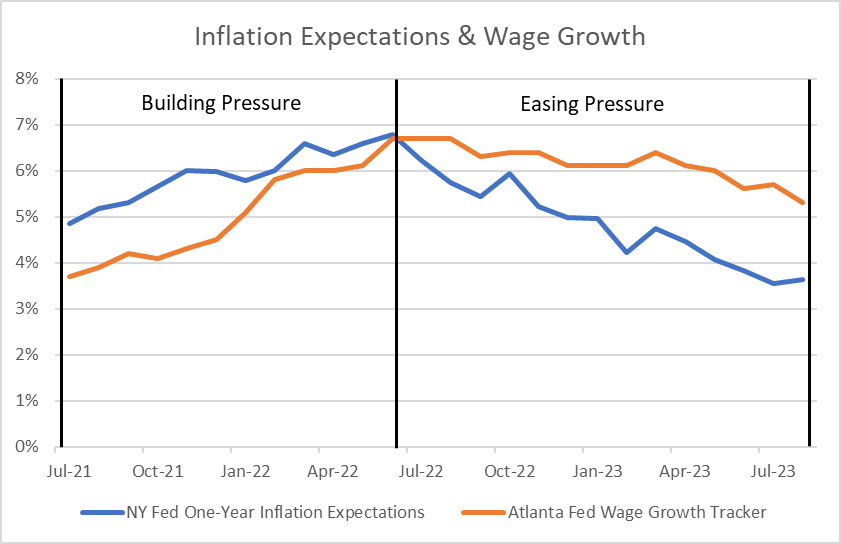

Once the Fed acknowledged that the post-pandemic rise in inflation was not “transitory”, its rhetoric underwent a stark shift towards a re-centering of its inflation mandate. This was highlighted by Chair Powell’s Jackson Hole speech from 2022, in which he eschewed the usual academic-type talk to forcefully iterate that the Fed’s, “overarching focus right now (was) to bring inflation back down to our 2% goal”. The rationale for this stance was both understandable and correct. Not only was the high level of inflation out of sync with the central bank’s price stability mandate, but the Fed was also concerned that high inflation could persist via a de-anchoring of inflation expectations. Such an outcome could lead to a self-perpetuating rise in wages and prices, making the job of returning inflation back to target much more painful for the economy.

While inflation is still well above target today, the fear of that sort of wage-price spiral has largely been assuaged. This is due to the fact that policy is now at an objectively restrictive level, and that both wage growth and inflation expectations have seemingly topped out.

Figure 4: New York Fed, Atlanta Fed, Bloomberg

It’s within this context that the idea that the Fed might tolerate inflation above 2% comes into play. As former Bank of England governor Adam Posen told Nick Timiraos of the WSJ, the Fed’s inflation target “is not meant to be an absolute rule.” He went on to state that “we should be understandably reluctant about crushing the economy to get from 3.5% to 2.25% inflation.” A similar point was echoed by Fed watcher Julie Cornado in an interview with Bloomberg. It’s not unreasonable to believe that at least some Fed officials also feel this way. Particularly if the economic outlook starts to weaken, the Fed may very well conclude that it’s willing to tolerate moderately above target inflation if it means that a recession or rise in unemployment is less likely.

If this happens, the logical endpoint of the action could be a widening of the Fed’s tolerance band for inflation, shifting the central tendency of inflation from the 1.5-2% level seen before the pandemic to something closer to 2-2.5%. Such an outcome would arguably be optimal for the Fed, as it could reduce the odds that the economy experiences deflation while at the same time resulting in a structurally higher neutral rate (in turn giving them more scope to cut rates in a downturn). And crucially, it would not be inconsistent with the Fed’s mandate.

Conclusion

In short, there are reasons to believe that short-term interest rates could remain above their post-financial crisis levels. Both cyclical and structural factors are supportive of a rise in the neutral rate, which is now being reflected in some models. This in turn could give the Fed scope to keep the Fed funds rate “higher for longer”. Eventually the Fed funds rate should converge towards the neutral rate, so with all things being equal, a higher neutral rate could equate to a higher path for the Fed funds rate.

This development should be a positive for the cash market space, as it portends that returns could be more competitive relative to the broader market. However, it is also relevant for firms seeking financing or looking to invest in new projects. After years of near-0% interest rates it may take time for companies to adjust to a world with higher hurdle rates and a greater cost of borrowing.

Please click here for disclosure information: Our research is for personal, non-commercial use only. You may not copy, distribute or modify content contained on this Website without prior written authorization from Capital Advisors Group. By viewing this Website and/or downloading its content, you agree to the Terms of Use & Privacy Policy.